Ground-Water Hydrology

of Prairie Potholes

in North Dakota

of Prairie Potholes

in North Dakota

By CHARLES E. SLOAN

HYDROLOGY OF PRAIRIE POTHOLES IN NORTH DAKOTA

GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 585-C

|

| Prairie potholes and fens |

|

| Coteau du Missouri |

Glacial drift west of the Coteau du Missouri consists mainly of thin ground moraine that is discontinuous and patchy near the Missouri River. West of the Missouri River, the drift is very discontinuous and, in many places, consists only of scattered erratics.

Coteau du Missouri

The Coteau du Missouri, or Missouri Plateau, is a large plateau that stretches along the eastern side of the valley of the Missouri River in central North Dakota and north-central South Dakota in the United States. This physiographic region of Saskatchewan and Alberta is classified as the uplands Missouri Coteau which is a part of the Great Plains Province or Alberta Plateau Region which extends across the south east corner of the province of Saskatchewan as well as the south west corner of the province of Alberta.[1]Historically, in Canada the area was known as the Palliser's Triangle regarded as an extension of the Great American Desert and unsuitable for agriculture and thus designated by Canadian geographer and explorer John Palliser. The terrain of the Missouri Coteau features low hummocky, undulating, rolling hills, potholes, and grasslands.[2]

The Coteau du Missouri, or Missouri Plateau, is a large plateau that stretches along the eastern side of the valley of the Missouri River in central North Dakota and north-central South Dakota in the United States. This physiographic region of Saskatchewan and Alberta is classified as the uplands Missouri Coteau which is a part of the Great Plains Province or Alberta Plateau Region which extends across the south east corner of the province of Saskatchewan as well as the south west corner of the province of Alberta.[1]Historically, in Canada the area was known as the Palliser's Triangle regarded as an extension of the Great American Desert and unsuitable for agriculture and thus designated by Canadian geographer and explorer John Palliser. The terrain of the Missouri Coteau features low hummocky, undulating, rolling hills, potholes, and grasslands.[2]

The plateau is poorly drained and is interspersed with glacial kettle lakes. It is transversed by several broad sags marking the ancient stream valleys of the eastern continuations of the Grand, Moreau, Cheyenne, Cheyenne River, Bad, and Whiterivers.

To the east of the plateau, the lowland valley of the James Riverwas formed by the lobe of the most recent ice age, separating the plateau from the Coteau des Prairies to the east.

Agriculturally the plateau is a grain and livestock region.

Cottonwood Lake Study Area North Dakota Wetlands

The Cottonwood Lake Study Area is located in Stutsman County, North Dakota, about 35 miles northwest of the Northern Prairie Wildlife Research Center (NPWRC) headquarters near Jamestown.

Today the Cottonwood Lake Study Area is internationally recognized as one of the most intensively studied wetland complexes in North America. More than 80 scientific publications, graduate theses, and presentations at scientific conferences resulting from these studies provide the bulk of information currently available to guide wetland management in the prairie pothole region of the U.S. and Canada. According to Euliss, one of the greatest contributions of theCottonwood Lake effort is that it "provides invaluable baseline data on the hydrological, chemical, and biological attributes upon which to base comparisons with ongoing research, including studies on wetland restoration and wetland monitoring." In addition, the understanding of the interrelation of hydrological, chemical, and biological processes revealed by research at the site provides the scientific foundation that allows wetland managers to understand the outcome of different management options.

|

| Cottonwood Lake area |

The Coteau des Prairies is a plateau approximately 200 miles in length and 100 miles in width (320 by 160 km), rising from the prairie flatlands in eastern South Dakota, southwestern Minnesota, and northwestern Iowa in the United States.

|

| Prairie Coteau of North Dakota. |

The southeast portion of the Coteau comprises one of the distinct regions of Minnesota, known as Buffalo Ridge.

The flatiron-shaped plateau was named by early French explorers from New France(Quebec), Coteaumeaning "slope"[citation needed] in French.

The plateau is composed of thick glacial deposits, the remnants of many repeated glaciations, reaching a composite thickness of approximately 900 feet (275 m). They are underlain by a small ridge of resistant Cretaceous shale. During the last (Pleistocene) Ice Age, two lobes of the glacier appear to have parted around the pre-existing plateau and further deepened the lowlands flanking the plateau.

The plateau has numerous small glacial lakes and is drained by the Big Sioux River in South Dakota and the Cottonwood River in Minnesota. Pipestonedeposits on the plateau have been quarried for hundreds of years by Native Americans, who use the prized, brownish-red mineral to make their sacred peace pipes. The quarries are located at Pipestone National Monument in the southwest corner of Minnesota and in adjacent Minnehaha County, South Dakota.

|

| Depth and location of Ogallala Aquifer |

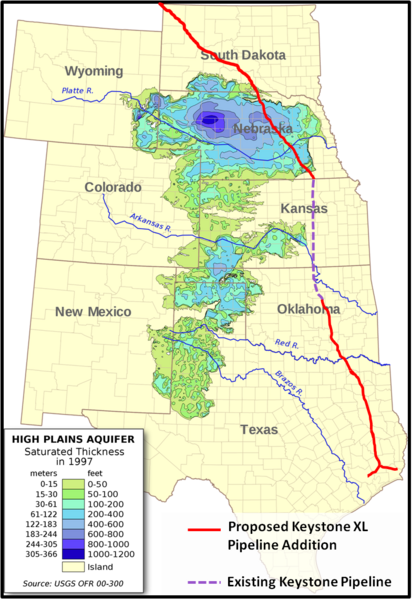

As may be seen from the map on your left, the ecologically sensitive areas under discussion that begin adjacent to the tar sands deposits in Alberta, Canada, continue into the High Prairie potholes of North Dakota, through the James River watershed, Cottonwood Lake and the COTEAU DU MISSOURI, andcrosses portions of the Ogallala Aquifer .

The underlying glacial pothole formations do not lend themselves to easy drainage, are susceptible to fluid transfers between layers, are permeable to exterior elements contamination, and exchange surface liquids with the underlying aquifer with ease.

The Ogallala aquifer has emerged as an important point in the debate. In June, two scientists from Nebraska called for a special study to determine how an oil spill would affect it, and Republican Sen. Mike Johanns of Nebraska has asked the State Department to consider an alternate, more easterly route that would avoid it. Twenty scientists from top research institutions recently signed a letter urging President Obama not to approve the pipeline because of environmental concerns.

Because it's the most heavily used aquifer in the United States and supplies about 30 percent of the groundwater pumped for irrigation nationwide. The Ogallala aquifer (also known as the High Plains aquifer) covers 175,000 square miles, an area larger than the state of California, and spans eight states — Nebraska, South Dakota, Wyoming, Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas and New Mexico.

A valve broke at a pumping station in southern North Dakota along the first leg of its Keystone pipeline system. The breach released about 500 barrels of Canadian heavy crude inside the facility and set off a geyser of oil that reached above the treetops in a nearby field. It was only ten months ago that the pipeline began transporting bitumen from Alberta's oil sands mines to refineries in Patoka, Illinois. ( Stacy Feldman, InsideClimate News and Elizabeth McGowan)

Needless to say, there can be no mistakes here, not with the lives,drinking water and food supply of millions Americans at risk. The ecosystems mentioned here are only the largest and most well known. From the arboreal forests of Alberta Canada, glacial tills of the High Plateau, the wetlands of the Dakotas and the Missouri River Watershed, the treasures of Utah, Nebraska all the way through Texas, this is a gift to be treasured and protected at all cost.

The certain ecological damage to wildlife and the natural resources of our Great Plains breadbasket is too precious to risk for a few drops of oil that will enrich only a few and do nothing to add to our American jobs or energy independence. Even if that were not true, we still could not afford this debacle. The destruction in Alberta, in our American west, the multiple dangers of pursuing these out dated and destructive projects is the epitome of arrogance. For only a fraction of the fortune that is being reaped from our lands, and investment of true American spirit, renewable energy could be ours in our lifetimes. As the space program was created and successfully implemented in the 1960's through sheer political will and popular support, so can we today continue creating the necessary energy technologies to eliminate the need for these destructive and fatal practices. It is the height of foolishness to even consider moving forward into the future with the old end game of dirty oil, toxic lands, polluted water and unbreathable air. Worse yet, to see all that is precious to us be destroyed by the avarice of greed and the Worship of Mammon would be a failing of monumental and irreversible proportions.

.jpg/800px-Missouri_Coteau_(656541298).jpg)