The Center for Public Integrity reports how a prominent law firm has withheld evidence of black lung in cases over the years, helping to defeat the benefits claims of sick miners.

Part Two: The Doctors

by Chris Hamby; Brian Ross; Matthew Mosk

The Center, in partnership with ABC News, reports on the crucial role played by doctors — including a unit at the nation’s top-ranked hospital — in helping to beat back miners’ benefits claims. Reports will appear on publicintegrity.org and abcnews.go.com, and televised segments will air on World News and Nightline.

Part Three: The Next Battleground

GLEN

FORK, W.Va. — Across Laurel Creek and down a dirt road in this

sleepy valley town is the modest white house where Steve Day grew up.

For more than 33 years, it was where he recuperated between shifts

underground, mining the rich seams of the central Appalachian

coalfields and doing his part to help make Peabody Energy Corp. the

nation’s most productive coal company. Now, it’s where he spends

most days and nights in a recliner, inhaling oxygen from a tank,

slowly suffocating to death.

More

than a half-dozen doctors who have seen the X-ray and CT images of

his chest agree he has the most severe form of black lung disease.

Yet his claim for benefits was denied in 2011, leaving him and his

family to survive on Social Security and a union pension; they

sometimes turn to neighbors or relatives for loans to make it through

the month.

The

medical opinions primarily responsible for sinking his claim didn’t

come from consultants-for-hire at a private firm or rogue doctors at

a fringe organization.

They

came from a respected household name: the Johns Hopkins Medical

Institutions.

The

Johns Hopkins University often receives attention for its medical

discoveries and well-regarded school of public health, and its

hospital recently was ranked the nation’s best by U.S. News and

World Report.

What

has remained in the shadows is the work of a small unit of

radiologists who are professors at the medical school and physicians

at the hospital. For 40 years, these doctors have been perhaps the

most sought-after and prolific readers of chest films on behalf of

coal companies seeking to defeat miners’ claims. Their fees flow

directly to the university, which supports their work, an

investigation by the Center for Public Integrity and ABC News has

found. According to the university, none of the money goes directly

to the doctors.

Their

reports — seemingly ubiquitous and almost unwaveringly negative for

black lung — have appeared in the cases of thousands of miners, and

the doctors’ credentials, combined with the prestigious Johns

Hopkins imprimatur, carry great weight. Their opinions often negate

or outweigh whatever positive interpretations a miner can produce.

For

the credibility that comes with these readings, which the doctors

perform as part of their official duties at Johns Hopkins, coal

companies are willing to pay a premium. For an X-ray reading, the

university charges up to 10 times the rate miners typically pay their

physicians.

Doctors

have come and gone from the unit over the years, but the leader and

most productive reader for decades has been Dr. Paul Wheeler, 78, a

slight man with a full head of gray hair and strong opinions.

In

the federal black lung system, cases often boil down to dueling

medical experts, and judges rely heavily on doctors’ credentials to

resolve disputes.

When

it comes to interpreting the chest films that are vital in most

cases, Wheeler is the coal companies’ trump card. He has

undergraduate and medical degrees from Harvard University, a long

history of leadership at Johns Hopkins and an array of presentations

and publications to his credit. In many cases, judges have noted

Johns Hopkins’ prestige and described Wheeler’s qualifications as

“most impressive,” “outstanding” and “superior.” Time and

again, judges have deemed him the “best qualified radiologist,”

and they have reached conclusions such as, “I defer to Dr.

Wheeler’s interpretation because of his superior credentials.”

Yet

there is strong evidence that this deference has contributed to

unjust denials of miners’ claims, the Center found as part of a

yearlong investigation, “Breathless and Burdened.” The Center

created a database of doctors’ opinions — none previously existed

— scouring thousands of judicial opinions kept by the Labor

Department dating to 2000 and logging every available X-ray reading

by Wheeler. The Center recorded key information about these cases,

analyzed Wheeler’s reports and testimony, consulted medical

literature and interviewed leading doctors. The findings are stark:

In

the more than 1,500 cases decided since 2000 in which Wheeler read at

least one X-ray, he never once found the severe form of the disease,

complicated coal workers’ pneumoconiosis. Other doctors looking at

the same X-rays found this advanced stage of the disease in 390 of

these cases.

Since

2000, miners have lost more than 800 cases after doctors saw black

lung on an X-ray but Wheeler read the film as negative. This includes

160 cases in which doctors found the complicated form of the disease.

When Wheeler weighed in, miners lost nearly 70 percent of the time

before administrative law judges. The Labor Department does not have

statistics on miners’ win percentage in all cases at this stage for

comparison purposes.

Where

other doctors saw black lung, Wheeler often saw evidence of another

disease, most commonly tuberculosis or histoplasmosis — an illness

caused by a fungus in bird and bat droppings. This was particularly

true in cases involving the most serious form of the disease. In

two-thirds of cases in which other doctors found complicated black

lung, Wheeler attributed the masses in miners’ lungs to TB, the

fungal infection or a similar disease.

The

criteria Wheeler applies when reading X-rays are at odds with

positions taken by government research agencies, textbooks,

peer-reviewed scientific literature and the opinions of many doctors

who specialize in detecting the disease, including the chair of the

American College of Radiology’s task force on black lung.

Biopsies

or autopsies repeatedly have proven Wheeler wrong. Though Wheeler

suggests miners undergo biopsies — surgical procedures to remove a

piece of the lung for examination — to prove their cases, such

evidence is not required by law, is not considered necessary in most

cases and can be medically risky. Still, in more than 100 cases

decided since 2000 in which Wheeler offered negative readings,

biopsies or autopsies provided undisputed evidence of black lung.

In

an interview, Wheeler held strongly to his views. In his telling, he

is more intellectually honest than other doctors because he

recognizes the limitations of X-rays and provides potential

alternative diagnoses, and he is adhering to a higher standard of

medical care by demanding biopsies to ensure patients get proper

treatment.

“I’ve

always staked out the high ground,” Wheeler said.

The

university defended Wheeler, saying in a statement he “is an

established radiologist in good standing in his field.”

For

decades, Dr. Paul Wheeler has led a unit of radiologists at Johns

Hopkins who often are enlisted by the coal industry to read X-rays in

black lung benefits cases. The Center for Public Integrity identified

more than 1,500 cases decided since 2000 in which Wheeler was

involved, reading a total of more than 3,400 X-rays. In these cases,

he never found a case of complicated black lung, and he read an X-ray

as positive for the earlier stages of the disease in less than 4

percent of cases. Subtracting from these the cases in which he

ultimately concluded another disease was more likely, this number

drops to about 2 percent.

|

| Normal chest X-ray |

University

officials questioned the findings by the Center and ABC, requesting

extensive documentation, which the news agencies provided. After

initially promising responses, officials at Johns Hopkins did not

answer most questions but instead provided a general written

statement.

“To

our knowledge, no medical or regulatory authority has ever challenged

or called into question any of our diagnoses, conclusions or reports

resulting from the … program,” the statement said.

After

the Center and ABC again posed questions about documents showing that

judges and government officials had challenged the opinions of

Wheeler and his colleagues on numerous occasions, university

officials sent the same statement again.

That

statement also said, “In the more than 40 years since this

program’s inception, [Johns Hopkins radiologists] have confirmed

thousands of cases to be compatible with [black lung].”

In

some cases reviewed by the Center and ABC, Wheeler opined that an

X-ray could be compatible with black lung but that another disease

was more likely, ultimately grading the film as negative.

The

news organizations asked the university how many times he had

provided a truly positive reading; Johns Hopkins officials would not

answer or clarify what they meant by “compatible.”

Judges

at varying times have called Wheeler’s opinions “disingenuous,”

“erroneous,” “troubling” and “antithetical to …

regulatory policy,” court records show.

One

judge dedicated an entire section of his ruling to the Johns Hopkins

specialists. Wheeler and two colleagues “so consistently failed to

appreciate the presence of [black lung] on so many occasions that the

credibility of their opinions is adversely affected,”

Administrative Law Judge Stuart A. Levin wrote in 2009.

“Highly

qualified experts can misread x-rays on occasion,” he wrote, “but

this record belies the notion that the errors by Drs. Wheeler [and

two colleagues] were mere oversight.”

|

| Chest X-ray w/ black lung |

But,

to discredit his readings and award benefits to a miner, as Levin

did, judges must identify a logical flaw or some other reason not to

give his opinion greater weight than those of other doctors. Former

judges said they knew certain doctors almost never found black lung,

but said they were barred from taking these experiences in other

cases into consideration. In four cases reviewed by the Center,

judges who have questioned Wheeler have seen their decisions vacated

by an appeals board.

Retired

judge Edward Terhune Miller, who often saw Wheeler’s opinions in

cases before him, said he sometimes was compelled to deny claims even

when he had serious doubts about the opinions of coal-company experts

from Hopkins and elsewhere. Miners often were unable to provide

enough evidence to overcome these opinions, and he wasn’t allowed

to take his personal knowledge of doctors’ tendencies into account.

“That’s one of the frustrations in the process,” said the

former judge. “There’s no doubt about it.”

Wheeler

said he is sure miners who don’t have black lung are being

wrongfully compensated. “They’re getting payment for a disease

that they’re claiming that is some other disease,” the doctor

said.

He

takes issue with a law passed by Congress in 1969 that was crafted to

lessen the burden of sick miners while limiting coal companies’

liabilities. Benefit payments for a miner start at just over $600 a

month and max out at about $1,250 monthly for a miner with three or

more dependents. Because these caps are low and miners are presumed

to be at a particular risk for the disease, the system does not

require they prove their cases beyond all doubt. Still, miners must

show that they have black lung and that, because of it, they are

totally disabled. About 85 percent of claims are denied at the

initial level.

“I

think if they have [black lung], it should be up to them to prove

it,” Wheeler said. To him, this means undergoing a biopsy. If

miners don’t submit to the procedure, he said, it suggests they may

be afraid the results will show they have something other than black

lung.

DR.

PAUL WHEELER, RADIOLOGIST FOR JOHNS HOPKINS

Biopsies

are rarely necessary to diagnose the disease and can put the patient

at risk, according to the American Lung Association, the National

Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), the Labor

Department, a paper published by the American Thoracic Society and

prominent doctors interviewed by the Center.

Told

his higher standard of proof, which he maintains is ordinary medical

practice, is not required by law, Wheeler held firm.

“I

don’t care about the law,” he said.

‘Victimized

twice’

To

people in the southern West Virginia town of Glen Fork, he is “Steve”

— longtime miner, father of three, Vietnam veteran. To Dr. Paul

Wheeler, from his vantage 400 miles away, he was “Michael S. Day

Sr.,” 58, another referral from corporate defense firm Bowles Rice

LLP.

Wheeler

has never been in a coal mine or met Steve Day. His opinion, though,

proved crucial in Day’s case.

In

2004, after more than three decades in jobs that exposed him to high

levels of dust, Day’s breathing worsened to the point his doctor

urged him to get out of mining. In January 2005, he filed a claim for

federal black lung benefits.

The

Labor Department pays for a medical examination by a doctor from an

approved list. Day unwittingly chose a doctor who commonly testifies

for coal companies, yet even this physician diagnosed the most

advanced stage of complicated black lung.

Then

the opinions from Johns Hopkins began arriving.

A

CT scan interpretation by Dr. John Scatarige, who is no longer at the

university: Large masses in the lungs, probably tuberculosis, or

maybe a fungal disease, or cancer. Black lung unlikely.

Two

X-ray readings by radiologist William Scott Jr., with the university

since the early 1970s: Large masses in the lungs, probably

tuberculosis. Black lung unlikely.

And,

most vitally, three X-ray readings and a CT scan interpretation by

Wheeler: Large masses in the lungs, probably tuberculosis,

histoplasmosis or a similar disease. Black lung unlikely.

Peabody

subsidiary Eastern Associated Coal Corp.’s chosen pulmonologist to

review the evidence, Dr. Robert Crisalli, originally found black lung

but changed his opinion after seeing Wheeler’s interpretations. He

adopted most of Wheeler’s views and testified, “The basis for the

conclusions primarily centers around the imaging, including the CT

scans.”

Day

lost.

A

spokesman for Peabody spinoff Patriot Coal Corp., which now owns the

subsidiary that employed Day, declined to comment, as did a

spokesperson for Peabody.

Like

many miners, Day relied primarily on the opinion of the doctor who

examined him for the Labor Department and the records from his

treatment over the years. He was at a distinct disadvantage, squared

off against the radiologists at Johns Hopkins.

In

determining Day didn’t have black lung, the Johns Hopkins experts

relied on the same criteria they have recited in countless cases

reviewed by the Center. Put simply, the white spots that show up on

film must have a particular shape, appear in a specific area of the

lung and follow a specific pattern.

At

the Center’s request, a physician not involved in the case, Dr.

John E. Parker, reviewed Day’s X-rays and CT scans taken between

2003 and 2012. Parker worked at NIOSH for 15 years, much of the time

as director of the X-ray surveillance program and the program to

certify qualified readers. He is now chief of pulmonary and critical

care medicine at the West Virginia University School of Medicine, and

travels the world teaching doctors to read X-rays in seminars, many

for NIOSH and the American College of Radiology.

|

| Steve Day, miner |

Parker

was told only Day’s name, age, number of years mining and the fact

that the interpretation of the films was disputed.

His

clear-cut conclusion: Complicated black lung. “Based on my findings

in reviewing this case, and the classic nature of the medical imaging

and history, I am deeply saddened and concerned to hear that any

serious dispute is occurring regarding the interpretation of his

classically abnormal medical imaging,” Parker wrote. “If other

physicians are reaching different conclusions about this case … it

gives me serious pause and concern about bias and the lack of

scientific independence or credibility of these observers.”

Told

later that Day had lost his case, Parker was taken aback.

“It

breaks my heart,” he said. “This man has been victimized twice —

once by the conditions that allowed him to get this disease and again

by a benefits system that failed him.”

Johns

Hopkins experts help defeat hundreds of claims

The

Center’s review of thousands of cases suggests there are many more

men like Day. Since 2000, miners have lost more than 800 cases after

at least one doctor found black lung on an X-ray but Wheeler read it

as negative. This includes 160 cases in which other doctors saw the

complicated form of the disease.

George

Hager, for example, worked in the mines for 37 years, and three

doctors saw complicated black lung on his X-rays and CT scan. Three

Johns Hopkins radiologists, including Wheeler, saw something else —

perhaps tuberculosis or histoplasmosis. The judge noted the

affiliation of the Johns Hopkins doctors and their “superior

qualifications.” Hager lost.

Douglas

Hall’s 27 years underground came to an end at the advice of his

doctor; he couldn’t walk 100 feet without struggling for breath.

Four doctors read his X-rays as complicated black lung, but, again,

three Hopkins radiologists, Wheeler among them, graded them as

negative, finding tuberculosis or histoplasmosis more likely. Though

tests for both diseases came back negative, Hall lost.

Keith

Darago initially won twice. Three doctors saw complicated black lung

on his X-rays and CT scans, and Administrative Law Judge Linda

Chapman rejected attempts by the three Johns Hopkins radiologists to

attribute the masses on the films to tuberculosis or a similar

disease, particularly given Darago’s negative tuberculosis test and

lack of history of any other disease.

But

the Benefits Review Board, the highest appeals court in the

administrative system, vacated the award of benefits twice and, at

the coal company’s lawyers’ request, referred the case to a

different judge. This time, the judge found the evidence on film to

be a wash. Darago lost.

Some

miners or their surviving family members continue to file claims,

occasionally winning after their disease worsens or they die. Others

simply give up, tired of fighting.

“I

think it’s a bad deal,” said Rodney Gibson, another miner whose

case followed a similar pattern. All the evidence of complicated

black lung he presented wasn’t enough. “They come out with a way

of getting around it somehow,” he said.

The

Center reports on the newest battle in the long-running war between

coal companies and miners, revealing the latest industry effort to

defuse emerging scientific evidence and contain its liabilities.

For

decades, Dr. Paul Wheeler has led a unit of radiologists at Johns

Hopkins who often are enlisted by the coal industry to read X-rays in

black lung benefits cases. The Center for Public Integrity identified

more than 1,500 cases decided since 2000 in which Wheeler was

involved, reading a total of more than 3,400 X-rays. In these cases,

he never found a case of complicated black lung, and he read an X-ray

as positive for the earlier stages of the disease in less than 4

percent of cases. Subtracting from these the cases in which he

ultimately concluded another disease was more likely, this number

drops to about 2 percent.

University

officials questioned the findings by the Center and ABC, requesting

extensive documentation, which the news agencies provided. After

initially promising responses, officials at Johns Hopkins did not

answer most questions but instead provided a general written

statement.

“To

our knowledge, no medical or regulatory authority has ever challenged

or called into question any of our diagnoses, conclusions or reports

resulting from the … program,” the statement said.

After

the Center and ABC again posed questions about documents showing that

judges and government officials had challenged the opinions of

Wheeler and his colleagues on numerous occasions, university

officials sent the same statement again.

That

statement also said, “In the more than 40 years since this

program’s inception, [Johns Hopkins radiologists] have confirmed

thousands of cases to be compatible with [black lung].”

In

some cases reviewed by the Center and ABC, Wheeler opined that an

X-ray could be compatible with black lung but that another disease

was more likely, ultimately grading the film as negative.

The

news organizations asked the university how many times he had

provided a truly positive reading; Johns Hopkins officials would not

answer or clarify what they meant by “compatible.”

Judges

at varying times have called Wheeler’s opinions “disingenuous,”

“erroneous,” “troubling” and “antithetical to …

regulatory policy,” court records show.

One

judge dedicated an entire section of his ruling to the Johns Hopkins

specialists. Wheeler and two colleagues “so consistently failed to

appreciate the presence of [black lung] on so many occasions that the

credibility of their opinions is adversely affected,”

Administrative Law Judge Stuart A. Levin wrote in 2009.

“Highly

qualified experts can misread x-rays on occasion,” he wrote, “but

this record belies the notion that the errors by Drs. Wheeler [and

two colleagues] were mere oversight.”

But,

to discredit his readings and award benefits to a miner, as Levin

did, judges must identify a logical flaw or some other reason not to

give his opinion greater weight than those of other doctors. Former

judges said they knew certain doctors almost never found black lung,

but said they were barred from taking these experiences in other

cases into consideration. In four cases reviewed by the Center,

judges who have questioned Wheeler have seen their decisions vacated

by an appeals board.

Retired

judge Edward Terhune Miller, who often saw Wheeler’s opinions in

cases before him, said he sometimes was compelled to deny claims even

when he had serious doubts about the opinions of coal-company experts

from Hopkins and elsewhere. Miners often were unable to provide

enough evidence to overcome these opinions, and he wasn’t allowed

to take his personal knowledge of doctors’ tendencies into account.

“That’s one of the frustrations in the process,” said the

former judge. “There’s no doubt about it.”

Wheeler

said he is sure miners who don’t have black lung are being

wrongfully compensated. “They’re getting payment for a disease

that they’re claiming that is some other disease,” the doctor

said.

He

takes issue with a law passed by Congress in 1969 that was crafted to

lessen the burden of sick miners while limiting coal companies’

liabilities. Benefit payments for a miner start at just over $600 a

month and max out at about $1,250 monthly for a miner with three or

more dependents. Because these caps are low and miners are presumed

to be at a particular risk for the disease, the system does not

require they prove their cases beyond all doubt. Still, miners must

show that they have black lung and that, because of it, they are

totally disabled. About 85 percent of claims are denied at the

initial level.

“I

think if they have [black lung], it should be up to them to prove

it,” Wheeler said. To him, this means undergoing a biopsy. If

miners don’t submit to the procedure, he said, it suggests they may

be afraid the results will show they have something other than black

lung.

“I

think if they have [black lung], it should be up to them to prove

it.”

DR.

PAUL WHEELER, RADIOLOGIST FOR JOHNS HOPKINS

Biopsies

are rarely necessary to diagnose the disease and can put the patient

at risk, according to the American Lung Association, the National

Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), the Labor

Department, a paper published by the American Thoracic Society and

prominent doctors interviewed by the Center.

Told

his higher standard of proof, which he maintains is ordinary medical

practice, is not required by law, Wheeler held firm.

“I

don’t care about the law,” he said.

Retired

miner Steve Day at his West Virginia home F. Brian Ferguson/Center

for Public Integrity

‘Victimized

twice’

To

people in the southern West Virginia town of Glen Fork, he is “Steve”

— longtime miner, father of three, Vietnam veteran. To Dr. Paul

Wheeler, from his vantage 400 miles away, he was “Michael S. Day

Sr.,” 58, another referral from corporate defense firm Bowles Rice

LLP.

Wheeler

has never been in a coal mine or met Steve Day. His opinion, though,

proved crucial in Day’s case.

In

2004, after more than three decades in jobs that exposed him to high

levels of dust, Day’s breathing worsened to the point his doctor

urged him to get out of mining. In January 2005, he filed a claim for

federal black lung benefits.

The

Labor Department pays for a medical examination by a doctor from an

approved list. Day unwittingly chose a doctor who commonly testifies

for coal companies, yet even this physician diagnosed the most

advanced stage of complicated black lung.

Then

the opinions from Johns Hopkins began arriving.

This

image, taken from a 2012 CT scan of Steve Day, shows a large mass in

each lung. Dr. John E. Parker, who used to run the government’s

X-ray surveillance program, says they represent a classic case of

complicated black lung.

A

CT scan interpretation by Dr. John Scatarige, who is no longer at the

university: Large masses in the lungs, probably tuberculosis, or

maybe a fungal disease, or cancer. Black lung unlikely.

Two

X-ray readings by radiologist William Scott Jr., with the university

since the early 1970s: Large masses in the lungs, probably

tuberculosis. Black lung unlikely.

And,

most vitally, three X-ray readings and a CT scan interpretation by

Wheeler: Large masses in the lungs, probably tuberculosis,

histoplasmosis or a similar disease. Black lung unlikely.

Peabody

subsidiary Eastern Associated Coal Corp.’s chosen pulmonologist to

review the evidence, Dr. Robert Crisalli, originally found black lung

but changed his opinion after seeing Wheeler’s interpretations. He

adopted most of Wheeler’s views and testified, “The basis for the

conclusions primarily centers around the imaging, including the CT

scans.”

Day

lost.

A

spokesman for Peabody spinoff Patriot Coal Corp., which now owns the

subsidiary that employed Day, declined to comment, as did a

spokesperson for Peabody.

Like

many miners, Day relied primarily on the opinion of the doctor who

examined him for the Labor Department and the records from his

treatment over the years. He was at a distinct disadvantage, squared

off against the radiologists at Johns Hopkins.

In

determining Day didn’t have black lung, the Johns Hopkins experts

relied on the same criteria they have recited in countless cases

reviewed by the Center. Put simply, the white spots that show up on

film must have a particular shape, appear in a specific area of the

lung and follow a specific pattern.

At

the Center’s request, a physician not involved in the case, Dr.

John E. Parker, reviewed Day’s X-rays and CT scans taken between

2003 and 2012. Parker worked at NIOSH for 15 years, much of the time

as director of the X-ray surveillance program and the program to

certify qualified readers. He is now chief of pulmonary and critical

care medicine at the West Virginia University School of Medicine, and

travels the world teaching doctors to read X-rays in seminars, many

for NIOSH and the American College of Radiology.

DOCUMENT

PAGES

NOTES

Zoom

«

Page

1 of 5

»

Parker

was told only Day’s name, age, number of years mining and the fact

that the interpretation of the films was disputed.

His

clear-cut conclusion: Complicated black lung. “Based on my findings

in reviewing this case, and the classic nature of the medical imaging

and history, I am deeply saddened and concerned to hear that any

serious dispute is occurring regarding the interpretation of his

classically abnormal medical imaging,” Parker wrote. “If other

physicians are reaching different conclusions about this case … it

gives me serious pause and concern about bias and the lack of

scientific independence or credibility of these observers.”

Told

later that Day had lost his case, Parker was taken aback.

“It

breaks my heart,” he said. “This man has been victimized twice —

once by the conditions that allowed him to get this disease and again

by a benefits system that failed him.”

Johns

Hopkins experts help defeat hundreds of claims

The

Center’s review of thousands of cases suggests there are many more

men like Day. Since 2000, miners have lost more than 800 cases after

at least one doctor found black lung on an X-ray but Wheeler read it

as negative. This includes 160 cases in which other doctors saw the

complicated form of the disease.

George

Hager, for example, worked in the mines for 37 years, and three

doctors saw complicated black lung on his X-rays and CT scan. Three

Johns Hopkins radiologists, including Wheeler, saw something else —

perhaps tuberculosis or histoplasmosis. The judge noted the

affiliation of the Johns Hopkins doctors and their “superior

qualifications.” Hager lost.

Douglas

Hall’s 27 years underground came to an end at the advice of his

doctor; he couldn’t walk 100 feet without struggling for breath.

Four doctors read his X-rays as complicated black lung, but, again,

three Hopkins radiologists, Wheeler among them, graded them as

negative, finding tuberculosis or histoplasmosis more likely. Though

tests for both diseases came back negative, Hall lost.

Keith

Darago initially won twice. Three doctors saw complicated black lung

on his X-rays and CT scans, and Administrative Law Judge Linda

Chapman rejected attempts by the three Johns Hopkins radiologists to

attribute the masses on the films to tuberculosis or a similar

disease, particularly given Darago’s negative tuberculosis test and

lack of history of any other disease.

But

the Benefits Review Board, the highest appeals court in the

administrative system, vacated the award of benefits twice and, at

the coal company’s lawyers’ request, referred the case to a

different judge. This time, the judge found the evidence on film to

be a wash. Darago lost.

Some

miners or their surviving family members continue to file claims,

occasionally winning after their disease worsens or they die. Others

simply give up, tired of fighting.

“I

think it’s a bad deal,” said Rodney Gibson, another miner whose

case followed a similar pattern. All the evidence of complicated

black lung he presented wasn’t enough. “They come out with a way

of getting around it somehow,” he said.

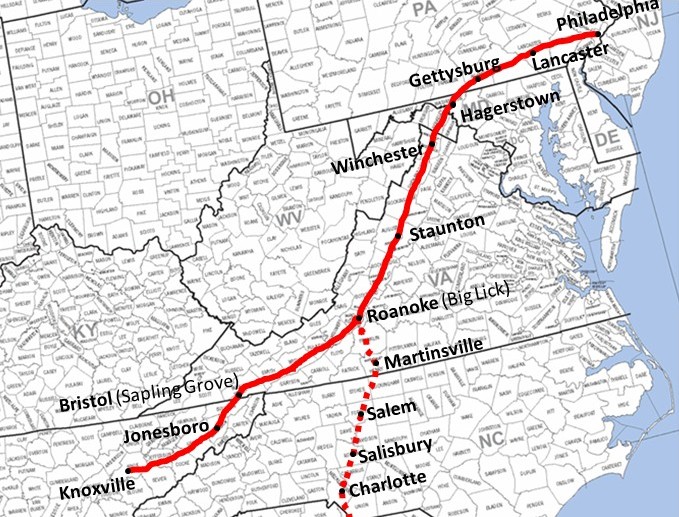

Normal

X-ray

Steve

Day’s X-ray

An

X-ray of Steve Day’s chest, taken in 2009, shows two large masses

(indicated by arrows). On previous films, Dr. Paul Wheeler said the

masses likely were caused by tuberculosis or a fungal infection from

bird and bat droppings. A half-dozen doctors have interpreted the

masses as complicated black lung. Dr. John E. Parker, who used to run

the government’s X-ray surveillance program, said this X-ray shows

a classic case of the severe disease. Mouse over the X-rays to

magnify the images. Images: Yale Rosen (left), licensed CC BY-SA;

courtesy of Steve Day family (right)

‘Not

using the system properly’

Wheeler

flips a switch, and a tall panel hums to life, emanating a white glow

in the dark corridor where the Pneumoconiosis Section, as the group

of Johns Hopkins radiologists is known, does its work. Papers bearing

the letterhead of prominent corporate defense law firms sit at work

stations, and stacks of folders in a storage closet have names of

firms and coal companies written in Sharpie on their sides.

Wheeler

places a series of chest X-rays against the panel and describes what

he sees.

He

moves to films showing large white masses. One doesn’t have small

spots surrounding it and is “pretty high [in the lung] — I would

call it out of the strike zone,” he says. He again suspects the

fungal infection. “If you want to bet against histoplasmosis,

you’re going to lose an awful lot,” he says.

These

X-rays, however, are not disputed films in a benefits case. They are

the standard X-rays that the government says show pneumoconiosis —

a family of disease that includes black lung and asbestosis, but not

histoplasmosis, tuberculosis and similar illnesses. When reading for

pneumoconiosis, government-certified readers are supposed to place

the unknown X-ray next to these films; they are classic cases meant

to be standards for comparison.

Wheeler

questions this and says the classification system has “some quality

issues.” He adds, “These are not proven.”

Experts

like Wheeler must pass an exam every four years to retain their

government certification. If a doctor were to classify these films as

negative during that exam, the physician very likely would fail, said

David Weissman, director of NIOSH’s Division of Respiratory Disease

Studies, which sets the standards for how readings should be

performed.

Wheeler,

however, has continued to pass the exam for decades, most recently

this April.

The

form used in the U.S. and many other countries for interpreting

X-rays contains boxes to grade what’s on the image and a comments

field for further explanation. If spots appear on the X-ray, a reader

is supposed to mark their size and shape, and then explain which

diseases seem more or less likely.

When

he reads X-rays for coal companies, however, Wheeler doesn’t do

this. If he sees spots on the film but thinks another disease is more

likely than black lung, he marks the film as negative. He typically

describes the abnormalities in the comments section, explaining why

they don’t meet his criteria for finding black lung. In case after

case reviewed by the Center, his comments were almost identical.

Weissman

said this approach is simply wrong.

“You’re

supposed to grade what’s there,” Weissman said. “You’re not

supposed to alter what the grade is based on what you think the

underlying cause is. That’s not using the system properly.”

In

a statement, university officials said the radiologists “adhere to

the clinical standards of diagnosis noted in the guidelines” put

forth by the International Labor Organization, upon which NIOSH

relies.

Wheeler

said he is being more responsible than other doctors by providing

multiple possible diagnoses. He often grades the film as negative but

says in the comments section that black lung is possible, but

unlikely.

The

practical effect of Wheeler’s readings: To rule out black lung.

Judges may consider the comments he writes, but the key, in comparing

Wheeler’s readings with others, is the negative numerical grade he

assigns.

In

depositions, he sometimes goes further to eliminate black lung as a

cause of a miner’s failing health. “He doesn’t have [black

lung],” he said in a 2004 case, for example. “[I]n no way is this

[black lung],” he said in another.

Weissman

said NIOSH often hears that some certified readers interpret X-rays

the way Wheeler does and that others over-diagnose diseases. “It’s

pretty frustrating sometimes when we hear of people that do well on

the exam and then go out in the real world and do other things,” he

said. “Absolutely that is a concern.”

The

agency’s authority, he said, doesn’t go beyond education,

training and administering the exam. People with complaints should

contact the state medical board, he said.

No,

by the numbers

There

is an unmistakable pattern in Wheeler’s readings. The Center

identified more than 1,500 cases decided since 2000 in which Wheeler

read at least one X-ray; in all, he interpreted more than 3,400 films

during this time.

The

numbers show his opinions consistently have benefited coal companies:

Wheeler

rated at least one X-ray as positive in less than 4 percent of cases.

Subtracting the cases in which he ultimately concluded another

disease was more likely, this number drops to about 2 percent.

In

80 percent of the X-rays he read as positive, Wheeler saw only the

earliest stage of the disease. He never once found advanced or

complicated black lung. Other readers, looking at the same images,

saw these severe forms of the disease on more than 750 films.

Where

other doctors saw black lung, Wheeler saw tuberculosis,

histoplasmosis or a similar disease on about 34 percent of X-rays.

This number shoots up in cases in which others saw complicated black

lung, which is so severe it triggers automatic compensation. In such

cases, Wheeler attributed the masses in miners’ lungs to these

other diseases on two-thirds of X-rays.

Asked

if he stood by this record, Wheeler said, “Absolutely.”

“I

have a perfect right to my opinion,” he added. “I found cases

that have masses and nodules. … In my opinion, those masses and

nodules were due to something more common.”

When

his views are questioned, Wheeler often shares anecdotes. He tells

the story of performing an autopsy during his residency on a woman

thought to have breast cancer; his examination revealed undetected

tuberculosis. Other common stories include his father’s severe

illness from histoplasmosis and a colleague’s bout with the

infection after spending a rainy night in an abandoned chicken coop.

In

a case decided in 2010, a doctor disputed Wheeler’s narrow view of

black lung, and the miner’s lawyer asked Wheeler during a

deposition whether he could cite medical literature to support his

views.

“I

don’t think I need medical literature,” Wheeler replied.

In

a 2009 letter submitted in another case, Wheeler questioned two

doctors who read X-rays as positive for black lung and wrote that he

and a colleague who had provided opinions in the case “are clinical

radiologists at one of the two or three best known hospitals in the

world.”

The

judge was not impressed. “This self-serving, egotistical diatribe

is unwarranted and very unprofessional,” he wrote.

Wheeler

took a similar approach in a recent interview, challenging the views

of any doctor, judge or organization — including the Labor

Department, NIOSH and the International Labor Organization — that

contradicted his. He said he’s never been told an interpretation of

his was wrong and he’d admit a mistake only if a biopsy or autopsy

showed black lung — and was performed by a pathologist with “proper

credentials.”

“I

know my credentials,” he said. “I’d like to make sure that the

people proving me wrong … have … credentials as good as mine.”

Proof

in the tissue

In

fact, tissue samples from miners’ lungs have proven Wheeler wrong

again and again.

The

pathologists providing the interpretations were enlisted by the coal

company in many cases, and they often came from well-regarded

academic medical centers, such as Washington University in St. Louis

and Case Western Reserve University, where Wheeler himself was a

resident. Some helped write widely accepted standards for diagnosis

of black lung with pathology and have been frequent experts for

companies defending claims.

Wheeler’s

readings were negative even in some cases in which the company

conceded the miner had black lung and chose to fight the claim on

other grounds.

When

clear pathology evidence did exist in cases reviewed by The Center,

it tended overwhelmingly to show that the doctors who had found black

lung — not Wheeler — were correct.

The

American Lung Association, NIOSH, the Labor Department and a paper

published by the American Thoracic Society say black lung usually can

be diagnosed with an X-ray, knowledge of the miner’s exposure to

dust and studies of lung function. Biopsies, which Wheeler insists

are “very safe,” are invasive, risky and usually unnecessary,

government officials and doctors said.

Still,

of the cases in which Wheeler submitted at least one negative

reading, miners or their surviving family members submitted evidence

from a biopsy or autopsy in more than 280 cases, a Center analysis

found. Contrary to Wheeler’s contentions, the pathology did not

resolve most cases. In about half, the tissue evidence proved

inconclusive or was disputed.

Of

the remaining cases, 75 percent revealed undisputed evidence of black

lung. In the other cases, the tissue did not show evidence of the

disease, but, as the law states, this doesn’t mean the miner didn’t

have black lung — only that it wasn’t present on the piece of

lung sampled.

In

the cases in which pathology showed Wheeler was wrong, other X-ray

readers saw black lung 80 percent of the time, and no interpretations

outside of Johns Hopkins existed in another 12 percent.

Most

times, then, only Wheeler and his Johns Hopkins colleagues failed to

see black lung.

Diagnosis

after death

Sometimes

miners had to die to prove they had black lung.

George

Keen worked 38 years in the mines and tried for 22 years to win

benefits. At least two physicians interpreted his X-rays and CT scans

as showing complicated black lung. Wheeler and his colleague Scott

read them as negative — probably tuberculosis, they said. Keen

lost.

Three

years after the most recent X-rays and CT scans read by Wheeler were

taken, Keen died. The company’s chosen pathologist agreed the

autopsy revealed complicated black lung.

John

Banks, who started loading coal by hand at 17, had multiple claims

denied. More than a half-dozen doctors saw black lung; Wheeler

suspected cancer. When Banks died, pathologists looking at his lung

tissue debated whether the disease had reached the complicated stage,

but both sides agreed: He had black lung.

Emily

Bolling suffered through much the same experience with her husband,

Owen, who spent most of the last six years of his life on oxygen but

wasn’t able to win benefits.

“They

would keep hiring more doctors and more doctors to read his X-rays,

and we had just one,” she said.

Wheeler

read a 2002 X-ray as negative. Owen died in 2003, and two

pathologists found that the autopsy showed black lung, allowing Emily

to win her widow’s claim. “It seems awful, but that’s what it

took,” she said recently. “It’s just wrong.”

Illene

Barr is trying to win benefits following the 2011 death of her

husband, Junior, who worked 33 years doing some of the dustiest jobs

in the mines. In his final years, his health progressively worsened.

“He loved to do things around the house,” Illene recalled. “He

had a garden. But he became so short-winded he couldn’t do any of

that. He ended up basically just sitting on the deck.”

He

lost claims in 2008 and 2010 after Wheeler read X-rays as negative,

saying histoplasmosis was much more likely.

“We

just couldn’t believe that it was happening,” Illene said.

Four

months after Wheeler’s most recent opinion that Junior likely was

suffering from the bird-and-bat-dropping disease, he died.

Pathologists for both sides saw black lung on the autopsy. Illene’s

benefits case is pending.

The

Wheeler standard

Wheeler

learned the strict criteria he applies from his mentor, Dr. Russell

Morgan, a revered figure at Johns Hopkins. In the early 1970s, Morgan

helped NIOSH develop the test to qualify as a “B reader” — a

doctor certified to read X-rays for black lung and similar diseases.

Wheeler served as one of his test subjects. The radiology department

bears Morgan’s name, and he went on to become dean of the medical

school.

Morgan

testified for companies defending a wave of lawsuits over

asbestos-related disease. Wheeler testified before Congress in 1984,

arguing that false asbestos claims were rampant and that plaintiffs

should prove their cases by undergoing a biopsy. He asserted that

similar problems existed in the black lung compensation system.

There

is general acknowledgement now that X-ray evidence was misused in

some asbestos claims. The black lung benefits system of today,

however, is a different universe.

In

some asbestos claims, plaintiffs won large verdicts or settlements,

and lawyers got rich. For black lung, the payouts are comparatively

meager — the maximum monthly payment, for miners with three or more

dependents, is about $1,250 — and few lawyers will take cases

because the odds of winning and ultimate compensation are low.

Settlements are not allowed, and miners have to prove total

disability caused by black lung, not just show a minimally positive

X-ray.

Wheeler

continues to express concerns similar to those he voiced in 1984. “It

comes down to ethics,” Wheeler said. “If you think it’s

appropriate for somebody with sarcoid to be paid for [black lung]

because he has masses and nodules — do you think that’s

appropriate? I don’t think so.”

After

Morgan’s death, Wheeler took over the “Pneumoconiosis Section.”

Asked if he viewed himself as the coal industry’s go-to

radiologist, Wheeler said: “Dr. Morgan was the go-to guy. … I’ve

replaced him … in the pneumoconiosis section, yes. … I can view

myself as the doctor for a number of companies, not just coal

companies.”

In

depositions and during the recent interview, Wheeler has insisted he

is relying on the criteria Morgan taught, praising his predecessor as

an innovator and genius. His criteria, however, do not comport with

mainstream views on black lung.

“When

you take this very strict view, where you put in all these rules,

none of which are a hundred percent, what will happen is you’ll

wind up excluding people that have the disease,” NIOSH’s Weissman

said.

According

to medical literature and experts consulted by the Center, black lung

does not always fit the narrow appearance Wheeler requires. Shown a

text, for example, that says the disease may affect one lung more

than the other, Wheeler said: “I don’t know where they get this

idea. … It’s not what Dr. Morgan taught me.”

In

fact, the statement comes from the standards established in 1979 by

the College of American Pathologists. The report was compiled by a

group of eminent doctors, including some who have testified regularly

for coal companies.

Doctors

interviewed by the Center said they had seen many cases of black lung

that did not fit Wheeler’s standards. “You’ll see a variety of

different presentations,” said Dr. Daniel Henry, the chair of the

American College of Radiology’s task force on black lung and

similar diseases. “The image can vary.”

In

one case decided in 2011, NIOSH got involved at the request of the

doctor who examined the miner for the Labor Department. Multiple

doctors had diagnosed complicated black lung, but Wheeler had read

X-rays as negative. The spots on the X-rays didn’t follow the

pattern he wanted to see, he’d said; histoplasmosis was more

likely.

Two

NIOSH readers, however, saw complicated black lung on the film, and

Weissman wrote a letter saying Wheeler’s views “are not

consistent with a considerable body of published scientific

literature by NIOSH.” The miner won his case.

Assumptions

and ‘bias’

A

pair of assumptions shapes Wheeler’s views in ways that some judges

and government officials have found troubling.

Former

miner Gary Stacy’s struggle for benefits lays bare the effects of

these beliefs.

When

he filed for benefits in 2005, Stacy was only 39 years old, yet three

doctors believed his X-rays and CT scans showed complicated black

lung. He had worked for almost 20 years underground and had never

smoked.

Wheeler,

however, read two X-rays as negative. He wrote that Stacy was “quite

young” to have complicated black lung, especially since the 1969

law required federal inspectors to police dust levels. Histoplasmosis

was much more likely, Wheeler thought.

A

judge denied Stacy’s claim in 2008, and it would take years of

fighting and a rapid decline in his breathing before he won.

In

reaching his conclusions about the cause of the large masses in

Stacy’s lungs, Wheeler drew upon beliefs that pervade his opinions:

Improved conditions in mines should make complicated black lung rare;

whereas, histoplasmosis is endemic in coal mining areas.

In

case after case, Wheeler has said complicated black lung was found

primarily in “drillers working unprotected during and prior to

World War II.”

Wheeler’s

contention contradicts a series of published studies by NIOSH

researchers showing that the prevalence of black lung actually has

increased since the late 1990s and that the complicated form

increasingly is affecting younger miners. Wheeler contends these

peer-reviewed studies aren’t conclusive because they have not been

confirmed by pathology.

Gary

Stacy is the kind of miner NIOSH says it now sees more often. Just 47

today, he appears trim and healthy, but a few minutes of conversation

reveal a different reality. His sentences are interrupted by hoarse

gasps for breath.

Stacy

now undergoes pulmonary rehabilitation to prepare for a lung

transplant. As his illness worsened, the evidence became

overwhelming, and his employer agreed to pay benefits.

The

fact that nothing in Stacy’s medical history indicated he’d

suffered from histoplasmosis or tuberculosis didn’t prevent

Wheeler’s readings from being credited in the 2008 denial. Someone

could be exposed, show no symptoms and still develop masses that

remain after the infection has fizzled out, Wheeler often has said.

This

is theoretically possible, said doctors consulted by the Center,

including an expert on histoplasmosis at the Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention. But, doctors noted, in cases with masses as

large as the ones Wheeler often sees on film, the patient likely

would show symptoms and have some record of the disease in his

medical history.

NIOSH’s

Weissman said the two diseases should rarely be confused on film.

“The appearance of [black lung] is different from the typical

appearance of … histoplasmosis,” he said. “That shouldn’t be

hard, in general, to make that differentiation.”

|

| Black lung-advanced Steve Day |

Wheeler’s

main alternative suggestion once was tuberculosis, but he has

switched to suggesting histoplasmosis more often. “Well, initially,

I thought TB was … causing these things,” he said in an

interview. Yet many of those cases, he now believes, “very likely

were [histoplasmosis].”

Could

he be wrong again? “I could be,” he said. “But I’d like to be

proven wrong with biopsies.”

In

written opinions, judges have said Wheeler’s assumptions seem to

have “affected his objectivity” and “inappropriately colored

his readings.” Another wrote in 2011 that Wheeler had a “bias

against a finding of complicated [black lung] in ‘young’

individuals.”

In

some cases, judges have questioned Wheeler’s demands for biopsy

proof and his speculative suggestions of other diseases. “The

reasonable inference to be drawn from Dr. Wheeler’s report and

testimony is that he does not accept a diagnosis of [black lung]

based on x-ray or CT scan alone,” one judge wrote in 2010.

Another

judge succinctly summarized Wheeler’s opinion: “I don’t know

what this is, but I know it’s not [black lung].”

Steve

Day, 67 F. Brian Ferguson/Center for Public Integrity

Scraping

to get by, struggling to breathe

Steve

Day’s wife, Nyoka, sleeps lightly. Most nights, they re-enact the

same scene.

Steve

sleeps upright in a recliner; if he lies flat, he starts to

suffocate. Nyoka lies in bed in the next room over, listening to his

breath and the hiss of the machine pumping oxygen through a tube in

his nose. She waits for the sound — a faint gasp.

“I

hurry in here, and I bend him over and say, ‘Steve, cough,’ ”

she said. “He’ll try and get by without having to cough because

it hurts. And I make him cough. I’ll scream at him, ‘Cough!’ ”

What

finally comes up is often black. They’ve made it through another

night.

This

is not the life they envisioned when Steve returned from Vietnam and

they eloped. Both of their fathers had worked in the mines, and both

had black lung. Before they got married, Steve made Nyoka a promise:

He’d never go to work in the mines.

It

wasn’t long before he changed his mind, persuaded by his father.

“He said that’s the only way you can make good money,” Steve

recalled of the job that, in good years, earned him as much as

$55,000 or $60,000. He worked just about every job underground. For

much of his career, he ran a continuous mining machine, which rips

through coal and creates clouds of dust.

“When

he came out of the mines, all you could see was his lips, if he

licked them,” Nyoka recalled. “He was black except around his

eyes.”

After

33 years in the mines, he thought the cause of his breathing problems

was obvious. So did his doctor, who is treating him for black lung.

The

reports from Johns Hopkins floored Steve and Nyoka. There was nothing

in his medical records to suggest he’d ever had tuberculosis or

histoplasmosis, let alone a case so severe that it left behind

multiple nodules and masses, including one occupying almost a third

of one of his lungs.

Steve

scowls at the mention of Wheeler’s name. “The more I talk about

him the madder I get,” he said. “And the madder I get, my blood

pressure shoots up.”

|

| Steve Day and family |

Administrative

Law Judge Richard Stansell-Gamm determined, based on the opinions of

Wheeler and the pulmonologist who adopted most of Wheeler’s

findings, that Day had not proven he had black lung. The judge didn’t

come to any conclusions about what caused Day’s severe illness.

He

lost his case on May 31, 2011, and, three days later, the Labor

Department sent Day a letter demanding $46,433.50. The department had

originally awarded Day’s claim in 2005 and started paying benefits

from a trust fund because the company’s lawyers had appealed. Now

that the initial award was overturned, the department wanted

reimbursement for what it paid out during the six years it took for

the case to reach a conclusion.

The

department eventually waived the so-called “overpayment” after

Day submitted documentation showing he had to support, to varying

degrees, eight other people with only Social Security and a union

pension.

“Each

person of age tries to help but overall it isn’t enough to survive

on without borrowing,” he wrote the department. “It has been very

humiliating to have to do so, when everyone knows that I worked my

life away from my children and my wife, in order to end up on full

time oxygen for a company who isn’t (decent) enough to acknowledge

the damage ‘their’ job done to my body, my life, and my family.”

Day

has not given up hope of winning benefits, but, if he files again, he

could find himself again having to overcome the opinions of Wheeler

and his colleague at Johns Hopkins.

As

he almost always does, Wheeler testified in Day’s case that he

should undergo a biopsy. Parker, the former NIOSH official who

examined Day’s X-rays and CT scans, said he’d advise against a

biopsy because the risk of complications for someone with Day’s

level of disease is too great.

That

leaves just one way, in Wheeler’s opinion, to disprove him. Steve

and Nyoka have already discussed it. “I done told her, ‘If

something happens to me, have an autopsy done on my lungs,’ ”

Steve said.

Since

he lost his case, Day’s breathing has declined. He began full-time

oxygen a year ago, but decided against a lung transplant. At 67, with

his health problems, he likely would not be a good candidate.

Miners

have developed a crude measure for how damaged their lungs are based

on how upright they need to be to sleep.

“You

start out with one pillow,” Nyoka said. “Then you go to two

pillows. Then three pillows, and that’s supposed to be your top.

Well, he went through that, and he got to where he couldn’t

breathe. So he got in the recliner, and he’s just lived in that

recliner for …”

“Years,”

Steve interjected, staring out the window toward the tree-lined

hillside.

“And

now the recliner,” Nyoka said. “It’s not enough.”

Editor’s

note: Brian Ross and Matthew Mosk work for ABC News. Retired judge

Edward Miller’s daughter is employed by the network. The Center

contacted him before ABC News joined the reporting for this story.