Compiled by

Dwight Collins

© reserved

Boreal Forest Region: Alberta, Canada

Boreal Forest Region: Alberta, Canada

Mighty rivers drain north and east from the Rocky Mountains into the watershed of the Arctic Ocean.

Look at any map of Alberta and you will see them: The Athabasca, Smoky, Peace, Chinchaga and Hay, tracing sinuous patterns across the vast northern half of the province, a lightly populated and little-known region of dark forests and muskegs.

This is the Boreal Forest Region which comprises 48 percent of Alberta.

The boreal forest is a critical ecosystem. The tar sands deposits lie in the boreal plains ecozone, which covers 183 million acres (74 million hectares) and extends across British Columbia, Northwest Territories, Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba. Forest cover is predominantly coniferous, and black spruce, white spruce, jack pine, and tamarack are principal species. Hardwoods, particularly trembling aspen, white birch, and balsam poplar, are well represented and are often mixed with conifers. This is one of the most productive forest areas not only in Canada, but in the entire world.

Approximately 35 percent of the boreal plains is composed of wetlands, including bogs, fens, swamps, marshes, and shallow open-water ponds. Some areas of the boreal plains have 85 to 95 percent wetland ground coverage, and these areas can stretch as wide as 120,000 acres (48,500 hectares). These extensive wetland and water areas combine with complex uplands to create a diverse mosaic of bird habitats. Most of these wetlands are connected through surface and groundwater hydrology and are highly susceptible to damage from tar sands development.

The tar sands cover 141,000 sq km of Alberta. Twenty per cent of this has 174billion recoverable barrels close enough to the surface to be strip-mined.

These incredible pictures show the bleak landscape of bitumen, sand and clay created by the frantic pursuit of 173billion barrels of untouched oil.

This is done by removing the forest and the peaty soil beneath, before gas-heated water is then forced through the tar sand to melt and separate bitumen from the sand and clay. It takes four barrels of water to retrieve one barrel of oil - creating large tailing ponds of oily, toxic water that covers vast expanses.

Lawyer and environmentalist Polly Higgins said: ‘Runaway climate change becomes almost inevitable if the tar sands continue.

‘The tar sands mining should be classified as an act of ecocide and rendered illegal under international law. This is, in effect, a crime against humanity.

----------------------------------------

Once this landscape was a pristine wilderness roamed by deer now it's 'the most destructive industrial project on earth'

Lush green forests once blanketed an area of the Tar Sands larger than England at Fort McMurray in Alberta, Canada,

- where blackened earth now stands, dubbed by environmentalists as most destructive industrial project on earth. Boreal forest - once home to grizzly bears, moose and bison - is vanishing at rate second to Amazon deforestation

Read more: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2219240/Tar-Sands-Canada-worlds-largest-oil-reserve-173billion-untouched-barrels.html#ixzz29iRMOGBH

Follow us: @MailOnline on Twitter | DailyMail on Facebook

----------------------------------------------------------------------

Enbridge Inc. is a Calgary, Alberta based

company focused on three core businesses: crude oil

and liquids pipelines, natural gas

transportation and distribution, and green energy

Enbridge operates the world's

longest crude oil and liquids pipeline system, located in both Canada and USA. It owns and operates Enbridge Pipelines Inc. and a

variety of affiliated pipelines in Canada and the U.S., and has an approximate

27% interest in Enbridge Energy Partners, L.P. (NYSE: EEP)

which owns the Lakehead System in the U.S. These pipeline systems

have operated for over 60 years and now comprise approximately 13,500

kilometres (8,400 mi) of pipeline, delivering more than 2 million barrels

(320,000 m3) per day of crude oil and liquids.

|

| Oil Pipeline stretching 1000's of miles |

Using data from Enbridge's

own reports, the Polaris Institute calculated that 804 spills occurred on

Enbridge pipelines between 1999 and 2010. These spills released approximately

168,645 barrels (26,812.4 m3) of crude oil into the

environment.[12]

|

| Enbridge Oil spill Yellowstone National Park, 2010 |

On July 4, 2002 an Enbridge pipeline ruptured in a marsh near the

town of Cohasset, Minnesota in Itasca County, spilling 6,000 barrels (950 m3) of

crude oil.

In 2006, there were 67 reportable spills

totaling 5,663 barrels (900.3 m3) on Enbridge's energy and

transportation and distribution system; in 2007, there were 65 reportable

spills totaling 13,777 barrels (2,190.4 m3) [14]On March 18, 2006, approximately 613 barrels (97.5 m3) of crude oil were released when a pump failed at Enbridge's Willmar terminal in Saskatchewan.[15] According to Enbridge, roughly half the oil was recovered.

On January 1, 2007 an Enbridge pipeline that runs from Superior, Wisconsin to near Whitewater, Wisconsin cracked open and spilled ~50,000 US gallons (190 m3) of crude oil onto farmland and into a drainage ditch.[16] The same pipeline was struck by construction crews on February 2, 2007, in Rusk County, Wisconsin, spilling ~201,000 US gallons (760 m3) of crude, of which only about 87,000 gallons were recovered. Some of the oil filled a hole more than 20 feet (6.1 m) deep and contaminated the local water table.[17][

In 2009, Enbridge Energy

Partners, a US affiliate of Enbridge Inc., agreed to pay $1.1

million to settle a lawsuit brought against the company by the state of Wisconsin for

545 environmental violations.[19]

In January 2009 an Enbridge

pipeline leaked about 4,000 barrels (640 m3) of oil southeast

of Fort

McMurray at the company's Cheecham Terminal tank farm

On January 2, 2010,

Enbridge's Line 2 ruptured near Neche, North Dakota, releasing about 3,784

barrels of crude oil, of which only 2,237 barrels of were recovered.[22][18]

July 2010, a leaking pipeline spilled an estimated 843,444 US gallons (3,192.78 m3) of crude oil into Talmadge Creek leading to the Kalamazoo River in southwest Michigan on Monday, July 26 near Marshall, Michigan.[24][25] A United States Environmental Protection Agency update of the Kalamazoo River spill concluded the pipeline rupture "caused the largest inland oil spill in Midwest history" and reported the cost of the cleanup at $36.7 million (US) as of November 14, 2011.[24] The cleanup is unfinished as of July 2012.[26]

Long involvement in Canada's tar sands has been central to Koch Industries' evolution and positions the billionaire brothers for a new oil boom.

According to Enbridge’s own

data, between 1999 and 2010, across all of the company’s operations there were

804 spills that released 161,475 barrels (approximately 25.67 million litres,

or 6.8 million gallons) of hydrocarbons into the environment

Bitumen from Canada's tar sands is dirtier and thicker than conventional

oil. Extracting and processing this unconventional fossil fuel creates far more

greenhouse gases than drilling for the light, sweet oil most Americans are

familiar with. Environmentalists, supported by many scientists, want tighter regulations

imposed on this crude to minimize its role in the U.S. economy as part of a larger effort to move beyond

petroleum

|

Mining operations in the Athabasca oil sands. Image shows the Athabasca River about 600m from the tailings pond. NASA Earth Observatory photo, 2009. |

Koch

Industries declined to answer any questions for this story.

-------------------------------------------------------------------

The controversy over the Kochs and the pipeline was sparked by an InsideClimate News report from February. That analysis, also published on Reuters.com and later cited by various news organizations, found that Flint Hills is deeply involved in the Canada-Alberta oil sands trade and is well positioned to benefit if more heavy crude is exported to the United States.

|

| A geyser of oil from a broken pipe in Burnaby in 2007 released 234,000 liters (aprox. 1500 barrels) before it was stopped. |

|

| Texas Fracking field |

http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2011/oct/05/koch-keystone-xl-pipeline

|

| Bullet causes oil spill in Alaska |

------------------------------------------------------------------

Out on the Tar Sands Mainline: Mapping Enbridge’s

Dirty Web of Pipelines

http://www.tarsandswatch.org/files/Updated%20Enbridge%20Profile.pdf

May 2010 (partially updated, March 2012).

The

Polaris Institute

For

more information on the Polaris Institute’s energy campaign please visit www.tarsandswatch.org

--------------------------------------------------------

The James River (also known as the Jim River or the Dakota River) is a tributary of the Missouri River, approximately 710 mi (1,143 km) long, draning an area of 20,653 square miles (53,490 km2) in the U.S. states of North Dakota and South Dakota.[1] The river provides the main drainage of the flat lowland area of the Dakotas between the two plateau regions known as the Coteau du Missouri and the Coteau des Prairies. This narrow area was formed by the lobe of a glacier during the last ice age, and as a consequence the watershed of the river is slender and it has few major tributaries for a river of its length

The river rises in Wells County, North Dakota, approximately 10 mi (16 km) northwest of Fessenden. It flows briefly east towards New Rockford, then generally SSE through eastern North Dakota, past Jamestown, where it is first impounded by a large reservoir (the Jamestown Dam), and then joined by the Pipestem River. It enters northeastern South Dakota in Brown County, where it is impounded to form two reservoirs northeast of Aberdeen. At Columbia, it is joined by the Elm River. Flowing southward across eastern South Dakota, it passes Huron and Mitchell, where it is joined by the Firesteel Creek. South of Mitchell, it flows southeast and joins the Missouri just east of Yankton.

Originally called "E-ta-zi-po-ka-se Wakpa," literally "unnavigable river" by the Dakota tribes, the river was named Rivière aux Jacques (literally, "James River" in English) by French explorers. By the time Dakota Territory was incorporated, it was being called the James River. This name was provided by Thomas L. Rosser, a former Confederate general who helped to build the Northern Pacific Railroad across North Dakota. A Virginian, he named the river and the settlement of Jamestown, North Dakota, after the English colony of Jamestown, Virginia. (The coincidence of the old French name "Jacques" directly translating as "James" in English is noted.) However, the Dakota Territory Organic Act of 1861 renamed it the Dakota River. The new name failed to attain popular usage and the river retains its pre-1861 name.

Ground-Water Hydrology

of Prairie Potholes

in North Dakota

of Prairie Potholes

in North Dakota

By CHARLES E. SLOAN

HYDROLOGY OF PRAIRIE POTHOLES IN NORTH DAKOTA

GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 585-C

|

| potholes Prairie-potholes-and-fens |

|

| Missouri River horseshoe bend |

Glacial drift west of the Coteau du Missouri consists mainly of thin ground moraine that is discontinuous and patchy near the Missouri River. West of the Missouri River, the drift is very discontinuous and, in many places, consists only of scattered erratics.

Coteau du Missouri

The Coteau du Missouri, or Missouri Plateau, is a large plateau that stretches along the eastern side of the valley of the Missouri River in central North Dakota and north-central South Dakota in the United States. This physiographic region of Saskatchewan and Alberta is classified as the uplands Missouri Coteau which is a part of the Great Plains Province or Alberta Plateau Region which extends across the south east corner of the province of Saskatchewan as well as the south west corner of the province of Alberta.[1] Historically, in Canada the area was known as the Palliser's Triangle regarded as an extension of the Great American Desert and unsuitable for agriculture and thus designated by Canadian geographer and explorer John Palliser. The terrain of the Missouri Coteau features low hummocky, undulating, rolling hills, potholes, and grasslands.[2]

The plateau is poorly drained and is interspersed with glacial kettle lakes. It is transversed by several broad sags marking the ancient stream valleys of the eastern continuations of the Grand, Moreau, Cheyenne, Cheyenne River, Bad, and White rivers.

To the east of the plateau, the lowland valley of the James River was formed by the lobe of the most recent ice age, separating the plateau from the Coteau des Prairies to the east. Agriculturally the plateau is a grain and livestock region.

Cottonwood Lake Study Area

North Dakota Wetlands

|

| Cottonwood Slough |

Today the Cottonwood Lake Study Area is internationally recognized as one of the most intensively studied wetland complexes in North America. More than 80 scientific publications, graduate theses, and presentations at scientific conferences resulting from these studies provide the bulk of information currently available to guide wetland management in the prairie pothole region of the U.S. and Canada. According to Euliss, one of the greatest contributions of the Cottonwood Lake effort is that it "provides invaluable baseline data on the hydrological, chemical, and biological attributes upon which to base comparisons with ongoing research, including studies on wetland restoration and wetland monitoring." In addition, the understanding of the interrelation of hydrological, chemical, and biological processes revealed by research at the site provides the scientific foundation that allows wetland managers to understand the outcome of different management options.

|

| Prairie Potholes |

The Coteau des Prairies is a plateau approximately 200 miles in length and 100 miles in width (320 by 160 km), rising from the prairie flatlands in eastern South Dakota, southwestern Minnesota, and northwestern Iowa in the United States.

|

| Prairie Coteau of North Dakota. |

The southeast portion of the Coteau comprises one of the distinct regions of Minnesota, known as Buffalo Ridge.

The flatiron-shaped plateau was named by early French explorers from New France (Quebec), Coteau meaning "slope"[citation needed] in French.

The plateau is composed of thick glacial deposits, the remnants of many repeated glaciations, reaching a composite thickness of approximately 900 feet (275 m). They are underlain by a small ridge of resistant Cretaceous shale. During the last (Pleistocene) Ice Age, two lobes of the glacier appear to have parted around the pre-existing plateau and further deepened the lowlands flanking the plateau.

The plateau has numerous small glacial lakes and is drained by the Big Sioux River in South Dakota and the Cottonwood River in Minnesota. Pipestone deposits on the plateau have been quarried for hundreds of years by Native Americans, who use the prized, brownish-red mineral to make their sacred peace pipes. The quarries are located at Pipestone National Monument in the southwest corner of Minnesota and in adjacent Minnehaha County, South Dakota.

|

| Depth and location of Ogallala Aquifer |

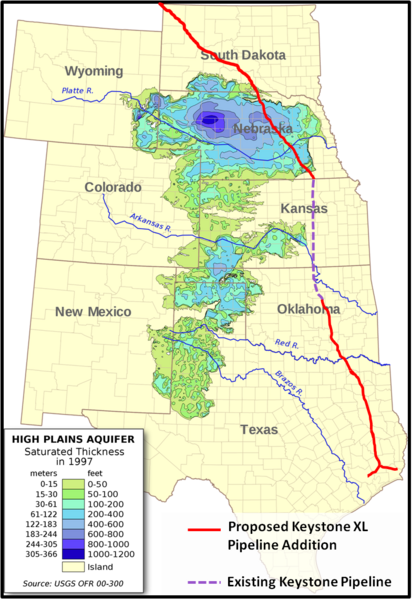

As may be seen from the map on your left, the ecologically sensitive areas under discussion that begin adjacent to the tar sands deposits in Alberta, Canada, continue into the High Prairie potholes of North Dakota, through the James River watershed, Cottonwood Lake and the COTEAU DU MISSOURI, and crosses portions of the Ogallala Aquifer .

The underlying glacial pothole formations do not lend themselves to easy drainage, are susceptible to fluid transfers between layers, are permeable to exterior elements contamination, and exchange surface liquids with the underlying aquifer with ease.

The Ogallala aquifer has emerged as an important point in the debate. In June, two scientists from Nebraska called for a special study to determine how an oil spill would affect it, and Republican Sen. Mike Johanns of Nebraska has asked the State Department to consider an alternate, more easterly route that would avoid it. Twenty scientists from top research institutions recently signed a letter urging President Obama not to approve the pipeline because of environmental concerns.

Because it's the most heavily used aquifer in the United States and supplies about 30 percent of the groundwater pumped for irrigation nationwide. The Ogallala aquifer (also known as the High Plains aquifer) covers 175,000 square miles, an area larger than the state of California, and spans eight states — Nebraska, South Dakota, Wyoming, Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas and New Mexico.

A valve broke at a pumping station in southern North Dakota along the first leg of its Keystone pipeline system. The breach released about 500 barrels of Canadian heavy crude inside the facility and set off a geyser of oil that reached above the treetops in a nearby field. It was only ten months ago that the pipeline began transporting bitumen from Alberta's oil sands mines to refineries in Patoka, Illinois. ( Stacy Feldman, InsideClimate News and Elizabeth McGowan)

|

Ogallala saturated thickness 1997 |

The following is an excerpt from “The Dilbit Disaster: Inside the Biggest Oil Spill You've Never Heard of,” a seven-month investigation by InsideClimate News

More than 1.1 million gallons of oil blackened two miles of Talmadge Creek and almost 36 miles of the Kalamazoo River, according to the EPA’s most recent Situation Report (pdf). The EPA’s estimate of the amount of oil that has been collected exceeds Enbridge’s estimate of 843,444 gallons by 15 percent. Enbridge spokeswoman Terri Larson told InsideClimate News that the company stands by that number as accurate.

Oil is still showing up two years later, as the cleanup continues. About 150 families have been permanently relocated and most of the tainted stretch of river between Marshall and Kalamazoo remained closed to the public until June 21.

The accident was triggered by a six-and-a-half foot tear in Line 6B, a 30- inch carbon steel pipeline operated by Enbridge Energy Partners LP, a U.S. affiliate of Enbridge Inc., Canada's largest transporter of crude oil. With Enbridge's costs already totaling more than $765 million, it is the most expensive oil pipeline spill since the U.S. government began keeping records in 1968.

Needless to say, there can be no mistakes here, not with the lives, drinking water and food supply of millions Americans at risk. The ecosystems mentioned here are only the largest and most well known. From the arboreal forests of Alberta Canada, glacial tills of the High Plateau, the wetlands of the Dakotas and the Missouri River Watershed, the treasures of Utah, Nebraska all the way through Texas, this is a gift to be treasured and protected at all cost. The certain ecological damage to wildlife and the natural resources of our Great Plains breadbasket is too precious to risk for a few drops of oil that will enrich only a few and do nothing to add to our American jobs or energy independence. Even if that were not true, we still could not afford this debacle. The destruction in Alberta, in our American west, the multiple dangers of pursuing these out dated and destructive projects is the epitome of arrogance. For only a fraction of the fortune that is being reaped from our lands, and investment of true American spirit, renewable energy could be ours in our lifetimes. As the space program was created and successfully implemented in the 1960's through sheer political will and popular support, so can we today continue creating the necessary energy technologies to eliminate the need for these destructive and fatal practices. It is the height of foolishness to even consider moving forward into the future with the old end game of dirty oil, toxic lands, polluted water and unbreathable air. Worse yet, to see all that is precious to us be destroyed by the avarice of greed and the Worship of Mammon would be a failing of monumental and irreversible proportions.

.jpg/800px-Missouri_Coteau_(656541298).jpg)

I get so sick when I hear some say the want more of this ugly mess.

ReplyDelete