Ted Drozdowski

|

12.17.2007

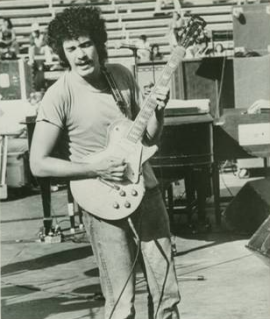

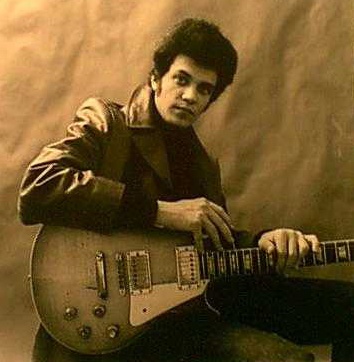

On a snowy New York night in 1965 a young, wiry guitarist named Michael Bloomfield

followed Bob Dylan into Columbia Records’ studio on Seventh Avenue

carrying a caseless, snow-covered Telecaster. Bloomfied knocked the snow

off his guitar, wiped it dry, plugged in, and revealed a glimpse of his

genius. It was quite an entrance—both literally and figuratively—to the

session that would yield “Like a Rolling Stone,” one of the greatest

rock and roll songs ever recorded, and to Bloomfield’s influential,

brilliant, and chaotic musical career.

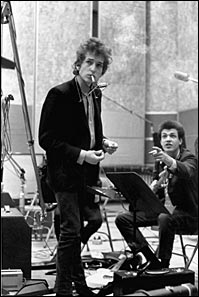

On a snowy New York night in 1965 a young, wiry guitarist named Michael Bloomfield

followed Bob Dylan into Columbia Records’ studio on Seventh Avenue

carrying a caseless, snow-covered Telecaster. Bloomfied knocked the snow

off his guitar, wiped it dry, plugged in, and revealed a glimpse of his

genius. It was quite an entrance—both literally and figuratively—to the

session that would yield “Like a Rolling Stone,” one of the greatest

rock and roll songs ever recorded, and to Bloomfield’s influential,

brilliant, and chaotic musical career.Later Kooper slipped back into the studio and faked his way through “Like a Rolling Stone” on Hammond organ, an instrument he could barely play at the time. So Bloomfield that afternoon not only cemented his own fame, but propelled Kooper into his gig as keyboardist in Dylan’s first electric band and his role as one of the most famous organists in rock and soul.

Bloomfield was already at work on another great album before he got the call for Dylan’s Highway 61 Revisited sessions: the Paul Butterfield Blues Band’s eponymous debut. His playing on the Nick Gravenites’ tune “Born in Chicago” and his own “Screamin’ ” on Butterfield Blues Band would become incendiary signposts for the genre’s future. But Bloomfield’s playing on Highway 61 is revolutionary.

Bloomfield was already at work on another great album before he got the call for Dylan’s Highway 61 Revisited sessions: the Paul Butterfield Blues Band’s eponymous debut. His playing on the Nick Gravenites’ tune “Born in Chicago” and his own “Screamin’ ” on Butterfield Blues Band would become incendiary signposts for the genre’s future. But Bloomfield’s playing on Highway 61 is revolutionary. His ringing licks on “Like a Rolling Stone” are among the most distinctive guitar signatures ever applied to a song. Jimi Hendrix copied them outright when he performed the tune. There’s also Bloomfield’s darting melodies and moaning bent-stringed solos on “Tombstone Blues;” his sensitive accompaniment to Dylan’s harmonica and piano on “It Takes a Lot to Laugh, It Takes a Train to Cry;” and his bell-like slide tones and shivering vibrato on the title track. Throughout the sessions Dylan’s spontaneous method of recording put Bloomfield’s improvisational skills and sonic vocabulary to the test, and the guitarist aced every turn. By the time the album was completed, 22-year-old Bloomfield had arrived at—and defined—the nexus of blues and rock, paving the way for the genre blending of Hendrix, Jeff Beck, Cream, and Led Zeppelin, all of whom followed in his wake.

Born in Chicago

By the time Dylan first encountered Bloomfield in a Chicago club in 1959 or ’60, the guitarist had abandoned his silver-spoon upbringing for the gritty stages of the South Side.

Bloomfield was born into a wealthy Jewish family in 1943 whose fortune was based on his father’s invention of the flapper-topped restaurant sugar dispenser. The Bloomfields also held patents for the revolving pie display case and a commercial coffee brewer, and ran a restaurant hardware supply and manufacturing company.

At

age 14, however, Bloomfield’s love for Elvis Presley and guitarist

Scotty Moore as well as the other Sun rockabilly cats led him to

recordings by bluesmen like Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf, who, he soon

discovered, were regularly playing in his own town.

At

age 14, however, Bloomfield’s love for Elvis Presley and guitarist

Scotty Moore as well as the other Sun rockabilly cats led him to

recordings by bluesmen like Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf, who, he soon

discovered, were regularly playing in his own town.Bloomfield chased the potent first-generation electric Chicago blues down in urban nightspots where few white people ventured. His youth and nervous energy made him stand out as much as the innate talent he displayed when he got on stage. Often he couldn’t contain his enthusiasm, leaping up with the likes of Magic Sam or Buddy Guy, plugging in, hitting notes and asking to sit in all at the same time.

It was easy for Bloomfield and other like-minded young white Chicago musicians to find each other in those clubs, so he and harmonica players Paul Butterfield and Charlie Musselwhite, and guitarists Nick Gravenites and Elvin Bishop all became blood brothers. Together they apprenticed on stage alongside idols like Muddy and Wolf.

As his playing developed, Bloomfield became especially interested in older bluesmen with acoustic roots. Hired to book the Fickle Pickle coffeehouse, Bloomfield scheduled nine-string guitarist Big Joe Williams, mandolinist Yank Rachell, guitarist Sleepy John Estes, and pianist Little Brother Montgomery specifically so he could play with them. He and Williams became especially close and recorded together several times.

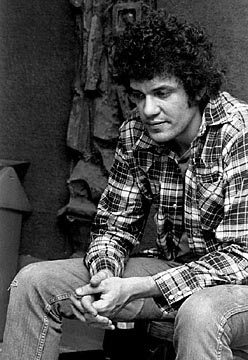

East-West

Before Dylan summoned him to New York, Bloomfield was at work on Butterfield Blues Band with his compatriots Butterfield, Bishop, Jerome Arnold, and Sam Lay. Regarded as the first integrated blues band, the group had found a natural leader in Butterfield—a smooth talker and soulful vocalist who, like many of his musical idols, carried a knife and took guff from few men. Soft-voiced Bloomfield, on the other hand, often spoke like a machine gun with a mechanism that occasionally jammed. He delivered words rapidly, then stammered, and often repeated himself or made unexpected leaps to other subjects mid-sentence. He was also subject to bouts with insomnia and depression. Ultimately, Bloomfield spoke most fluidly through his instrument, expressing his thoughts and emotions in a sonorous tone he could ply in all directions, from needling staccato licks to burnished metallic sliding to warm wail-and-moan bends to dark sustained notes singing with vibrato.

After the Highway 61 Revisited sessions, Bloomfield also joined Dylan’s road band for a short time, making him a member of two of the finest ensemble groups of the day. By then he had assimilated what he could from the Chicago masters and built on his finger-picking, devouring records by country guitar kingpin Merle Travis and the ragtime style of Blind Blake.

Bloomfield rarely used fingerpicks or thumbpicks, and usually only with lap resonator and steel guitars. He preferred the organic tone generated by plucking strings with his fingers or thumbnail, or by using his index finger nail as a pick. (For a detailed overview of Bloomfield’s command of blues styles, check out his semi-instructional album If You Love These Blues, Play ’em As You Please, reissued on CD in 2004.)

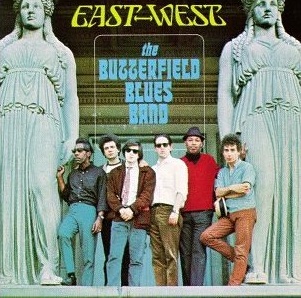

Highway 61 Revisited introduced Bloomfield to the mainstream, but the second Butterfield Blues Band recording, 1966’s East-West,

had a profound effect on the world of guitar. His playing on the album

is as knotty, dramatic, and unpredictable as his increasingly troubled

spirit. The tune “East-West,” a 13-minute exploratory fusion of blues

and Indian modality that showcased Bloomfield and Bishop, flipped the

switch for long-form rock improvisation. Thus Bloomfield ran

neck-and-neck with Eric Clapton, transporting blues into the psychedelic

era. This was a calculated move for the Butterfield Band, who saw their

blues heroes marginalized as musical styles transformed and evolved

without them. Despite their devotion to the music’s roots, tracks like

“East-West” and their wild on-stage musical explorations—comparable to

those of their Elektra Records label mates the Doors—kept them utterly

contemporary.

Highway 61 Revisited introduced Bloomfield to the mainstream, but the second Butterfield Blues Band recording, 1966’s East-West,

had a profound effect on the world of guitar. His playing on the album

is as knotty, dramatic, and unpredictable as his increasingly troubled

spirit. The tune “East-West,” a 13-minute exploratory fusion of blues

and Indian modality that showcased Bloomfield and Bishop, flipped the

switch for long-form rock improvisation. Thus Bloomfield ran

neck-and-neck with Eric Clapton, transporting blues into the psychedelic

era. This was a calculated move for the Butterfield Band, who saw their

blues heroes marginalized as musical styles transformed and evolved

without them. Despite their devotion to the music’s roots, tracks like

“East-West” and their wild on-stage musical explorations—comparable to

those of their Elektra Records label mates the Doors—kept them utterly

contemporary.Bloomfield’s genius intensifies every track on East-West. His shimmering slide licks and shrieking, treble-toned lead on “Walking Shoes,” akin to Hubert Sumlin’s playing on Howlin’ Wolf classics like “Killing Floor,” are ghostly, needling, vicious, and unforgettable. On the band showcase “Work Song,” Bloomfield’s melodies climb through scales in a manner closer to free-jazz saxist John Coltrane than to B.B. King—another of his influences balancing chromatic ascents and descents with radically slurred bends and off-the-beat accents. And Bloomfield’s linear single-note playing on “I Got a Mind to Give Up Living,” which acknowledges his debt to King with wrist-shaking vibrato, captures the soulful essence of simmering slow blues.

Goldtops and Sunbursts

During the recording of East-West, Bloomfield acquired an early ’50s Les Paul Goldtop—the same model Muddy Waters preferred in the early days of his first electric band. Its P-90s scream, cry, and sigh all over the album, from the chug and moan of “Work Song” to the glistening slide of “Walking Shoes,” to the raga-esque pinnacle of the title track. The Goldtop gave Bloomfield everything he wanted from a guitar: big, bold tones for rhythm playing and full throttle wailing, and delicate butterfly evocations of notes when it came time to play sweet and cool.

Though Bloomfield was not a fan of distortion, he loved volume. He preferred to run his Les Paul through loud, clean amps with plenty of headroom. Nonetheless, Jimmy Page, who primarily earned his reputation as a gunslinger in the studio and on stage with the Yardbirds while wielding other models, adopted the Les Paul under the influence of Bloomfield and the Paul became his trademark after the first Led Zeppelin album.

A few years later Bloomfield acquired another Les Paul, a sunburst 1959 Les Paul Standard, from Dan Erlewine, guitarist for Ann Arbor, Michigan’s the Prime Movers. Today Erlewine is one of the world’s leading luthiers, but then he was just starting out, and a Bloomfield acolyte smitten with the slightly older guitarist’s range and depth.

Bloomfield remained a Les Paul fan for the rest of his life. A 1979 story in Guitar Player magazine described Bloomfield’s affection for the instruments, which he allowed to accumulate dust and grime in his messy home, but then cleaned up perfunctorily for sessions and performances—much like he did with the snow-covered Tele he brought into the studio with Dylan.

The Butterfield Band’s rising rock scene popularity, aided by their apoplexy-enducing appearance with Dylan at Newport in 1965 and by East-West’s acclaim, made them regulars at San Francisco’s Fillmore Auditorium. Bloomfield became increasingly smitten with the city’s “love crowd,” as Otis Redding called the West Coast’s flower power generation, and the musicians on the scene. In San Francisco he also began using heroin, which would ultimately play a heavy role in his undoing and complicate his already difficult personality. Bloomfield left Chicago and moved to San Francisco in 1967.

During the city’s Summer of Love, Bloomfield formed the Electric Flag with fellow Windy City ex-pats Nick Gravenites and organist Barry Goldberg. The group also included Buddy Miles, who would later be part of Hendrix’s Band of Gypsys. The group’s goal was to expand all its members’ horizons. Miles’ gritty red-clay voice gave them license to explore soul and R&B, and the interests of the other members pushed the Flag to assimilate blues, country, rock, and folk into their palette.

Their first recording was the aptly unfocused soundtrack for The Trip, a merrily lurid movie about an LSD experience starring Peter Fonda and Dennis Hopper, written by Jack Nicholson and directed by low-budget exploitation flick notable Roger Corman. But their real coming out party was the Monterey Pop Festival in July, where 55,000 attendees warmly received them.

Although by all accounts Bloomfield’s Goldtop-fueled performance was ferocious, but he was convinced the Electric Flag had not hit its mark at Monterey. It was the beginning of his disillusionment with the band.

The next year, the Flag released their official debut A Long Time Comin’. It immediately became a staple of FM radio, which was emerging at the time as an outlet of the rock-fueled counterculture, an alternative to the pop-oriented, music industry dictated sound of the AM airwaves. Despite Bloomfield’s heroic turns on Howlin’ Wolf’s “Killing Floor” and the then-anthemic original “Groovin’ is Easy,” the album is no work of genius. The horns are banal and distracting, and the textbook pop arrangement of “Groovin’ is Easy” seems to undermine its message of freedom. No wonder Bloomfield left that same year.

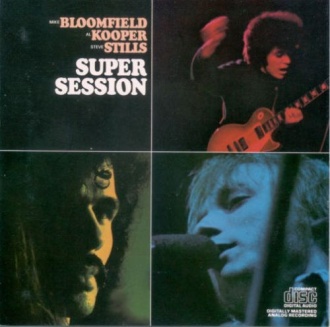

Super Session

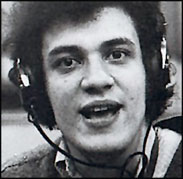

Al Kooper and Michael Bloomfield had become close friends after the Highway 61

sessions. Today Kooper asserts that he has a wealth of unheard

Bloomfield tracks awaiting a worthwhile opportunity for release. But

back in ’68, the keyboardist and producer saw his friend foundering

after he split the Electric Flag.

Al Kooper and Michael Bloomfield had become close friends after the Highway 61

sessions. Today Kooper asserts that he has a wealth of unheard

Bloomfield tracks awaiting a worthwhile opportunity for release. But

back in ’68, the keyboardist and producer saw his friend foundering

after he split the Electric Flag.Early that year Kooper and Bloomfield had been part of a jam for Moby Grape’s Wow album. Kooper was already well-aware of Bloomfield’s improvisational talents. After that reminder he conceived of recording a jam session to showcase Bloomfield. The idea was not only to give his favorite guitarist a vehicle to restore the luster on his star, but to carry over a concept from jazz to the rock world. Many jazz albums were made around a leader/composer who was teamed with carefully chosen sidemen. Once in the studio, they’d improvise on tunes and cut a disc.

So Kooper booked two days of studio time in L.A. and called in bassist Harvey Brooks and Goldberg from the Electric Flag and drummer Eddie Hoh. The first day’s nine-hour session was a delight. Bloomfield and Kooper meshed beautifully on the guitarist’s “Albert’s Shuffle” and “Really,” the experimental “His Holy Modal Majesty,” songwriter Jerry Ragovoy’s “Stop” and Curtis Mayfield’s “Man’s Temptation,” burning some of Bloomfield’s most emotive playing to tape. And then, in the throes of insomnia or, as it’s been often speculated, a fit of drug-fueled feverishness, Bloomfield packed up that night unbeknownst to Kooper and fled for home.

When Kooper discovered what had happened the next day, he saved the session by calling in Buffalo Springfield guitarist Stephen Stills. Their jamming yielded an alluring version of Donovan’s “Season of the Witch” and enough additional cuts to complete the Super Session album.

Despite its rocky start, Super Session was a smash so a sequel, The Live Adventures of Mike Bloomfield and Al Kooper, was made over three September 1968 nights at San Francisco’s Fillmore West. Kooper had learned his lesson, so chose to record on Bloomfield’s turf in case complications arose. Even at that, Bloomfield, who apparently had been up with insomnia for five days before the first gig on the 26th, didn’t complete the project. The third night Kooper got a call informing him that Bloomfield was in the hospital being sedated to sleep. Elvin Bishop and Carlos Santana filled in.

Desolation Row

Sadly,

there were few musical triumphs in the remainder of Bloomfield’s

career. For the next 13 years he ricocheted between occasional live

performances, uneven recordings for a series of mostly independent

labels and outright disappearances from the music scene.

Sadly,

there were few musical triumphs in the remainder of Bloomfield’s

career. For the next 13 years he ricocheted between occasional live

performances, uneven recordings for a series of mostly independent

labels and outright disappearances from the music scene.On his solo debut It’s Not Killing Me, whose title may well have been a rationalization for his drug abuse, Bloomfield chose to subsume his guitar playing to the songs. Guitar heads generally despise it and, indeed, if not for his mellow, gently melodic singing, Bloomfield would seem like just another member of the sprawling ensemble cast.

More notable is 1973’s Triumvirate, which teamed Bloomfield with New Orleans hoodoo piano man Dr. John and fellow blues singer-guitarist John Hammond. The session’s uneven, but sloppy versions of John Lee Hooker’s “Groundhog Blues” and the Crescent City funker “Cha-Dooky-Doo” make it seem like the recording process was enjoyable, and Bloomfield sounds like himself again—especially on the latter’s closing solo—even if he’s often too low in the mix.

There are at least a few compelling songs on all of his releases for John Fahey’s Takoma Records label in the 1970s. That said, it’s hard to describe any of the studio recordings Bloomfield made until his death in 1981 as “essential.” There is one exception, 1979’s If You Love These Blues, Play ’me As You Please, which originally appeared as a joint project by Guitar Player magazine and Takoma. The 2004 reissue CD also includes acoustic guitar duets Bloomfield recorded with Woody Harris for the Kicking Mule label. Combined, the 31 tracks trace every vein of Bloomfield’s roots, from African-American work songs to Appalachian spirituals to T-Bone Walker swing to primal country. It’s a delightful excursion that captures Bloomfield absolutely inspired, perhaps by the challenge of exploring so many styles in-depth. And it features the guitarist explaining his amp and guitar choices for each track, the genesis of each number, the keys and further salient details.

The other notable disc from Bloomfield’s later years is the live At the Old Waldorf (1976 –’77). It proves that even at a period when his struggles with heroin, his personal demons and perhaps, as has been reported, arthritis were eroding his musical abilities, when he was on, he was uncanny. Bloomfield held down a gig at San Francisco’s Old Waldorf nightclub most weekends during that period, and his lead playing on numbers like Lightnin’ Hopkins’ “Feel So Bad,” the Elmore James classic “The Sky is Crying” and his lifelong friend Gravenites’ “Buried Alive in the Blues” and “Bad Luck Baby” comes on like a forest fire.

Sadly, At the Old Waldorf was a posthumous release. Any musical or personal issues Bloomfield had were resolved at the end of a needle just two years after he made If You Love These Blues… He was found dead from an overdose in his car, parked on a side street in San Francisco on February 15, 1981.

The circumstances of his fatal fix remain a mystery. Some of his friends theorized that he OD’ed elsewhere and was driven to the spot where he was discovered, probably to avoid trouble for his fellow users. At any rate, for Michael Bloomfield, one of the finest guitarists in American music, death came unnecessarily and far too soon. He was 37.

No comments:

Post a Comment