zach.carter@huffingtonpost.c

PADUCAH, Ky. -- Ever since the U.S. government's uranium

enrichment plant started hiring in 1951, there has been a Buckley

helping to run it. Before his sons, a daughter-in-law and a grandson

clocked in, Fred Buckley, now 86, would travel three hours a day from

his home in West Tennessee to make $1.46 per hour as a plant security

guard.

It felt to Buckley like he was back in the Army, working with a

close-knit group of men on a secret mission. He'd served in World War II

-- after a few weeks of basic training, he ended up on the front lines

at the Battle of the Bulge. He rose quickly from infantryman to staff

sergeant to squad leader. The job at the plant promised the safety of a

stable income and a sense of purpose at the dawn of the Cold War. One

month before he started, the first of his two sons was born.

It seemed like

Paducah

was being reborn too. As new workers from neighboring Illinois, Ohio

and Tennessee showed up, the small city in Western Kentucky faced a

housing shortage. "So many people came in, you know?" Buckley told The

Huffington Post. "Anything that had a roof on it -- chicken house, any

kind of outbuilding, they were in it."

Room rates tripled until local officials imposed rent control. Home

construction blanketed the city, while trailer parks rose up on cinder

blocks throughout the surrounding county. More than 1,100 homes were

built while Buckley waited for his chance to move to the Paducah area.

After more than six years, he found a one-story, two-bedroom white frame

house on a corner lot off Highway 60, just three miles from the plant.

He still lives there today.

The flood of well-paid men had ramifications well beyond the

homebuilding industry, lifting almost every business in the region. Even

the local

brothel expanded.

Paducah embraced the plant and its patriotic celebration of nuclear

power. It called itself "The Atomic City" and envisioned thoroughfares

bright with shiny, pastel-colored automobiles, a downtown humming with

Cold War money. "The plant just made the town, you know?" Buckley says.

He still remembers when they first raised the American flag in front of

the plant's administration building. He was there, standing at

attention.

Fred Buckley (left) with the Paducah plant union's vice president, Jim Key.

Nobody understands the plant's importance more than Mitch McConnell.

For the past 30 years, the Senate minority leader, now 71, has been the

plant's most ardent defender in Washington. The Republican lawmaker

knows

its 750 acres

located just 12 miles from downtown. He's walked its grid under the

haze of the ever-present steam cloud emanating from its cooling towers.

He grasps its history, its hold on the imaginations of men like Buckley.

No other jobs in Western Kentucky presented the opportunity to use more

electricity than Detroit and more water than New York City every day of

the week.

The senator has remained loyal to the plant and its workers, keeping

it running on federal earmarks and complicated deals with the Department

of Energy to convert its core function from producing warheads to

mining nuclear waste to create electricity. At least in Paducah,

McConnell is not the "abominable no-man," the sour-faced persona of

Washington gridlock. He is an honorary union man. "He's been the best

friend to the plant we've had over the years," Buckley says. "He went

above and beyond the call of duty for the union."

Up until the tea party-led ban on earmarks a few years ago, McConnell

played out this dichotomy across Kentucky. In Washington, he voted

against a health care program for poor children. In Kentucky, he

funneled money to provide innovative health services for pregnant women.

In Washington, he railed against Obamacare. In Kentucky, he supported

free health care and prevention programs paid for by the federal

government without the hassle of a private-insurance middleman. This

policy ping-pong may not suggest a coherent belief system, but it has

led to loyalty among the GOP in Washington and something close to fealty

in Kentucky. It has advanced McConnell's highest ideal: his own

political survival.

McConnell's hold on Kentucky is a grim reminder of the practice of

power in America -- where political excellence can be wholly divorced

from successful governance and even public admiration. The most dominant

and influential Kentucky politician since his hero Henry Clay,

McConnell has rarely used his indefatigable talents toward broad,

substantive reforms. He may be ruling, but he's ruling over a

commonwealth with the

lowest median income

in the country, where too many counties have infant mortality rates

comparable to those of the Third World. His solutions have been

piecemeal and temporary, more cynical than merciful.

And with McConnell's rise into the GOP leadership, his continuous

search for tactical advantage with limited regard for policy

consequences has overrun Washington. McConnell has more than doubled the

previous high-water mark for the number of filibusters deployed to

block legislation, infamously declaring that his "

top political priority"

was to make President Barack Obama a one-term president. This

obstruction has had serious consequences, as the Great Recession grinds

on and large-scale problems like climate change march inexorably

forward. Congress has failed to address the nation's most pressing

challenges, and America has come to look more and more like McConnell's

Kentucky.

At the Paducah plant, and throughout the Bluegrass State, McConnell's

influence is a complicated, even poisonous one. As other aging nuclear

facilities have been shuttered, Paducah has groaned its way into the

21st century. The plant has become a barely functional relic in the

midst of a decades-long power down. The town's post-war pastels have

given way to rust, padlocks and contaminated waterways. After three

decades under McConnell, Kentucky residents are wondering whether his

survival is good for them.

Up for reelection again in 2014, McConnell faces dismal polling numbers. In January, a

Courier-Journal Bluegrass Poll found that only 17 percent of residents said they were planning on voting for him. A recent

Public Policy Polling survey

showed him tied in a hypothetical race against Alison Lundergan Grimes,

Kentucky's Democratic secretary of state, weeks before she announced

she was running on July 1. Today, McConnell finds himself at both the

most powerful and most vulnerable moment of his career. He faces not

only a Democratic opposition out to avenge McConnell's attacks on Obama,

but an energized tea party unhappy with the GOP establishment and

independents disgusted with Washington.

Keith Runyon was a veteran reporter and editorial page editor for the

Louisville-based Courier-Journal, Kentucky's dominant statewide paper,

which has generations of close personal ties to state and national

Democrats. He witnessed McConnell's rise in Louisville and its suburbs

of Jefferson County. He met his future wife, Meme Sweets, when she

worked as McConnell's press secretary after his election as the county's

judge-executive. Runyon came to know McConnell well. He says that

McConnell was not always such a ruthless partisan obstructionist.

"It was not the local Mitch McConnell that became the problem," he

told HuffPost. "It was what he became when he went to Washington."

In 2006, the former editor and publisher of the liberal Courier-Journal,

Barry Bingham Jr., 72, "was dying and knew it," Runyon says. A week before his death in early April, he summoned Runyon to his home.

When he arrived on that balmy morning, Runyon recalls, Bingham was

sitting up in a chair in his library. A breeze was drifting in through

the windows. Among the many things Bingham wanted to talk about, the

paper's early support of McConnell was one them. "He looked at me and he

said, ‘You know, the worst mistake we ever made was endorsing Mitch

McConnell' in 1977."

MODERATE MITCH

Squint long enough and hard enough, and you can see vestiges of the

young, moderate McConnell in his funneling of federal money toward

Kentucky projects. This is the McConnell who forged a political identity

at the elbow of Kentucky's iconic reformer Republicans, the McConnell

who didn't just admire Martin Luther King Jr., but made a point of

witnessing the March on Washington from the Capitol steps and later

spoke up for the cause on his University of Louisville campus.

In the summer before he began law school at the University of

Kentucky, McConnell went to Washington as an intern for Kentucky's

beloved Republican statesman, Sen.

John Sherman Cooper.

The senator had helped draft the first legislation for federal

education aid, had fought school discrimination and had been a

co-sponsor of the bill that created Medicare. He'd been hit with a lot

of flak back home for the health care legislation, but his experiences

taught him a bleak lesson.

"I noticed that the old country doctors and the country officials --

people who had been out in the country and had seen the plight of the

people who live in the hollows and down the dirt roads -- they were for

it,"

Cooper told reporters in 1972.

"And I remembered my experiences as county judge in Pulaski County,

when I'd go out in the county and see these people -- desperate, hungry,

sick and nowhere to turn, and no one to help them except the old

country doctors. You just can't let people go hungry. You can't just let

them lie there sick, to die. Not in this country. Not with all we've

got."

Cooper had also been an ardent supporter of one of Lyndon Johnson's

signature achievements, the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and helped defeat

the filibuster against it. The summer after his internship, "Cooper

grabbed a visiting McConnell by the arm and spontaneously took him to

the Capitol" where the two watched Johnson sign the Voting Rights Act of

1965, according to John David Dyche's

Republican Leader, a biography of McConnell.

McConnell later joined

Marlow Cook's

campaign for Senate in 1968, as a field organizer at colleges across

the state. By the time he was through, every campus had a Cook group. "I

think he believed in what we were doing," Cook says. "He believed that

we were trying to bring a moderate Republican to succeed a moderate

Republican. As a Republican, I was the one that could do that."

After the successful campaign, McConnell joined Cook's staff in

Washington where he worked with the senator to pass the Equal Rights

Amendment, which would have guaranteed equal rights for women. Cook says

McConnell and his staff all "had to work like hell on it." The

amendment passed but ultimately failed to be ratified by enough states

to be written into the Constitution. Cook had been

the only Republican leading the deeply controversial effort. "We were fighting the likes of

Phyllis Schlafly that didn't want women in the military," Cook explains. "All the churches were against it."

John Yarmuth, another young reform-minded Republican, crisscrossed

the state with McConnell campaigning for Cook, and remembers McConnell

as pro-choice and a supporter of Planned Parenthood. Yarmuth says that

after his stint with Cook, McConnell boasted about his work on behalf of

the Equal Rights Amendment.

Yarmuth

himself is now serving a fourth term in the House of Representatives,

after switching parties to become a Democrat in the mid-1980s.

Back home, Louisville in the 1970s was experiencing a progressive heyday. The city's new Democratic mayor,

Harvey Sloane,

a doctor by trade, had spent two years in Appalachia as part of

President John F. Kennedy's health care initiative. In Louisville, he

set up a health center that served primarily African Americans in the

West End neighborhood, which helped him launch a political career. As

mayor, Sloane started an emergency medical service and helped create a

public transportation system. Neighborhoods began to invest in historic

preservation. The county started an ecology court to tackle

environmental crimes.

"The community was in a can-do frame of mind," Sloane recalls. "Those

were times where people were willing to step up to the plate."

The city still had plenty of problems that needed solving, of course,

with deeply entrenched racism at the forefront. In 1975, courts ordered

local officials to implement a new busing program in an effort to

desegregate the school system. For a time,

uglier forces prevailed.

The Klan showed up and mass anti-busing demonstrations were held. After

a calm first day of school, mobs burned buses, attempted to block

firefighters from putting out blazes and attacked the police. The

National Guard had to be brought in to restore order.

McConnell had witnessed government's righteous potential under Sens.

Cooper and Cook, and he wanted to lead it. As Dyche notes in his

biography, McConnell tried to distinguish himself during Watergate by

coming out for campaign finance reform in a Courier-Journal op-ed: "Many

qualified and ethical persons are either totally priced out of the

election marketplace or will not subject themselves to questionable, or

downright illicit, practices that may accompany the current electoral

process." McConnell called for dramatic reductions in campaign

contribution limits and labeled the idea of a city-run campaign trust

fund a "progressive" proposal.

In 1977, he decided to challenge Democrat Todd Hollenbach Sr. for

Jefferson County judge-executive, a job that exercises administrative

authority over the Louisville suburbs and some city functions like

welfare. The job had oversight over the most populous county in the

state.

Hollenbach confesses today that he did not consider McConnell a

threat. "First time I ever saw him, I must admit I was amused," he said.

"I just didn't take him seriously. I can remember thinking to myself,

‘I bet he carried a briefcase in the third grade.' I thought he was just

a comical-looking kind of character. ... He had no personality. He was

very uncomfortable in a crowd."

But McConnell had a message that was independent enough to gain

traction. There were roads that required fixing, cronyism that needed

stamping out and a jail whose locks could be broken with a toothbrush.

"He was kind of a good-government guy," remembers

Meme Sweets Runyon,

who worked as McConnell's campaign coordinator and later became his

press secretary. "He thought the government could do good and could be a

solution."

Charles Musson, a campaign staffer who also later worked in the

McConnell administration, agrees: "He wanted to make sure government was

effective."

Position papers and campaign strategy were formed in McConnell's

basement during brainstorming sessions -- much of it aimed at reaching

working-class Democrats. "Mitch would ask questions, and someone would

be assigned to do research on that and become the expert on that,"

Musson remembers. McConnell worked the fried-fish-and-fried-chicken

circuit. Some mornings, he served coffee to workers arriving for their

shift at the General Electric plant.

McConnell came out in favor of collective bargaining rights for

workers and netted the endorsement of the Greater Louisville Central

Labor Council. One of his most heavily run ads featured McConnell

walking with Cooper, highlighting the young politician's ties to the

progressive GOP's old guard.

Dyche reports in his biography that the young politician's message

did not include any Republican branding. "Breaking with local

tradition," Dyche wrote, "he ran his campaign independently from the

Jefferson County GOP apparatus and refused to share a slate with the

Republican candidates in other races down the ballot."

While he used negative ads to batter Hollenbach -- most notably one

that featured a farmer arguing that Hollenbach's statements on taxes

amounted to shoveling manure -- Musson and Dyche recall McConnell

showing a soon-to-be-discarded restraint. He chose not to run an ad

addressing the court-ordered busing that had caused so much upheaval two

years earlier. Hollenbach had no say over the busing but had fought it

in court in an embarrassing and losing effort. Another potential ad

featuring the young victims of a high-profile traffic accident was

similarly deemed insensitive.

McConnell sealed his victory with the surprise endorsement of the

editorial board of the Courier-Journal. The young politician told

Louisville Today that the daily's nod showed voters that "the community

isn't going to go to hell if you have a Democratic mayor and a

Republican county judge. It's OK to split your ticket."

Once in office, McConnell governed with bipartisanship in mind. He

became "very good" at compromising, Musson says. He hired some of

Louisville's leading feminists for his inner circle and began forming

coalitions with his Democratic counterparts on the county legislature.

"He expected more from me and thought I could do more than I did for

myself," Meme Sweets Runyon says. "He demanded a lot from me and

insisted that I could do it."

McConnell sought to diversify the county's powerful boards and

commissions, which had great sway over planning and development, and had

historically been stacked with elites.

He invested in significantly expanding the

Jefferson Memorial Forest,

adding close to 2,000 acres. His administration also replaced trees

uprooted by a tornado. "He was always willing to support green things if

you made a good case for it," says Runyon, noting that he also started

an office dedicated to environmental issues and had a well-respected

liberal run it.

McConnell became known for his insistence on quality personnel. There

were no more jailbreaks with toothbrushes. "He believed in things like

historic preservation and the environment and functional social

services," Runyon adds.

During his second term, McConnell worked closely with the progressive

Sloane. If he took a position that might appear hostile to the

Louisville mayor, McConnell would give him a warning. "He would call me

and explain where he's coming from," Sloane remembers. "There wasn't

personal acrimony there. I did the same thing with him." J. Bruce

Miller, the Democratic county attorney, says McConnell had the same deal

with him.

McConnell joined forces with Sloane to attempt a county-city merger

as a way of cutting duplicative services and infusing suburban wealth

into the city. It was a fairly liberal idea that proved ahead of its

time. The referendum failed twice during their terms, but finally passed

in 2000 and went into effect a few years later.

On the merger project, Sloane said the two didn't disagree a lot. "I

think he was shrewd, and he did attract some good people," he said. "He

wasn't intimidated by progressive people and thinking. [The merger

attempt] didn't help either of us. I give him some respect for that. …

He was very pragmatic. We were not there to be ideologues."

'BAD DOGGY'

On the stump, McConnell likes to tell a story about an encounter with

a tobacco farmer during one of his early Senate campaigns. "I'm for

you," McConnell recalls the farmer telling him. "And what's more, you're

going to win." The tale has multiple iterations -- sometimes it takes

place in Western Kentucky in Graves County; at other times, McConnell

leaves the location vague. But the story always has the same punch line:

McConnell, a Louisville politician, asks the farmer why he's so sure

McConnell will be victorious. "That feller," the farmer explains, "he's

from

Louie-ville."

"I believe you're right," McConnell tells the farmer, and walks on.

McConnell looks like a guy who would foreclose on your farm. The senator has

a net worth

of somewhere between $9.2 million and $36.4 million, according to his

latest financial disclosure filings. Yet he has so much rural

authenticity that small-town voters mistake him for one of their own.

McConnell's communion with the working class isn't the result of any

intuitive genius. He studied farmers and coal miners for years,

cultivating an understanding of the issues and anxieties that dominate

rural Kentucky. He learned to hang.

"He can get down on the level with anybody," says Mary Canter, who

has worked for a decade at the Graves County Republican Party office.

"He can come down to just the average John IQ." Although Canter has met

McConnell many times, she can't say where he lives. His credibility is

so well established that his background isn't questioned.

Even in his early years campaigning for Cook, McConnell made it a

point to respect the local language. Yarmuth remembers getting lost in

Appalachia with McConnell. When they finally stopped and asked for

directions, "It's right back there," the man told them, down "the road a

couple hollers."

Yarmuth, a lifelong Louisvillian, recalls asking the man, "How loud the hollers?"

But McConnell understood, quickly ended the interaction and told

Yarmuth to get in the car. In Kentucky, a holler or hollow is an address

-- a nook or cranny in a mountain where a family builds a home. In

locales without official roads or house numbers, "the next holler over"

can be the best way to give directions.

McConnell capitalizes on his country cachet with ads accusing his

opponents of being inauthentic creatures of the political machine. The

first and most notorious was

a cold-blooded ad he

ran in his first Senate race in 1984 against Walter "Dee" Huddleston,

an ad that became infamous for debasing the tone of national campaigns.

Although

Huddleston had one of the strongest attendance records in Congress, he had missed a few votes while giving paid speeches. McConnell's

"Hound Dog" ad,

produced by future Fox News chief Roger Ailes, featured a man with a

pack of dogs searching for Huddleston. It was funny, wry and gently

mocking, but the effect was devastating.

Huddleston didn't think anyone would fall for the ad. "I thought the

bloodhounds were kind of silly, but as it went on, I thought it was

pretty effective," he told HuffPost. "It wasn't true."

The ad was so effective that McConnell

spit out a sequel in which the man chases an actor playing Huddleston up a tree.

It was a sign of things to come, and the launch of a long arc in a

lengthy and controversial career. Once McConnell won high office and

moved to Washington, his embrace of the broad uses of government

dwindled, and he came more and more to focus his career on the goal of

acquiring power.

By 1990, when Sloane took on McConnell for his Senate seat, the old

respect between the two men had gone out the window. On the stump,

McConnell called for abolishing campaign donations from political action

committees, yet by October he had taken close to $900,000 in PAC money.

He deployed class-war tactics, calling Sloane his "millionaire

opponent" for holding stock in oil companies, although McConnell and his

campaign were highly favored by the industry. "Just remember: Every

time the price of gas goes up, rich people like Harvey get richer -- and

Kentucky families get poorer. We need to fight back," McConnell argued.

McConnell's campaign even came out and said he was open to raising

taxes on the wealthy by eliminating some deductions. In a TV ad, he

professed the belief that "everyone should pay their fair share" in

taxes, "including the rich."

The central selling point of Sloane's campaign was his long

dedication to universal health care. McConnell tried to steal his

message with a weak proposal providing meager tax credits and tort

reform. He used his own childhood bout with polio to obscure the

limitations of his plan. "When I was a child, and my dad was in World

War II, I got polio," he said in another ad produced by Ailes. "I

recovered, but my family almost went broke. Today, too many families

can't get decent, affordable health care. That's why I've introduced a

bill to make sure health care is available to all Kentucky families,

hold down skyrocketing costs, and provide long-term care."

No attack was too personal for McConnell. Sloane had been caught

prescribing himself pain medications with a Drug Enforcement

Administration registration number that had expired three years earlier.

The Kentucky Board of Medical Licensure eventually cleared him, and

Sloane even took a drug test proving he was no addict. Yet McConnell

hyped the whole controversy in an ad seemingly inspired by "

Reefer Madness."

As the camera flashed to pills and vials, a voice-over described Sloane

as downing a "powerful depressant" and "mood altering" drugs.

"I got releases by my physicians that this wasn't the case," Sloane,

who had a chronic back injury and a bad hip that would need to be

replaced immediately following the election, told HuffPost. "What else

can you do?"

Sloane went down in defeat.

Miller, the elected county attorney who worked alongside McConnell,

says the senator is a formidable opponent in part because he focuses

relentlessly on politics. Miller recalls throwing a Valentine's Day

party that McConnell attended. After making small talk with McConnell

about the Super Bowl, a friend pulled Miller aside in exasperation. The

friend, Miller says, couldn't believe McConnell didn't know who had

actually played in the game.

McConnell used to invite Miller out for dinner about three times a

year. "It always centered around politics," Miller says, of their social

interactions. If there was any conversation about their children,

Miller says he'd be the one to bring it up. "He had daughters, and I

would be the one that would have to initiate a discussion of them. ...

He knew I had a son who was a professional golfer at the time. ... If I

asked him about his daughters, he wouldn't say, 'Tell me about your

son.'"

"He's intense," Miller says. "It's almost single-minded intensity.

I'm not being critical of it. That's why everybody got beat by the guy."

McConnell kept producing animal-themed attack ads that made "

The Dukes of Hazzard"

look like Shakespeare, with messages so over-the-top as to mock the

hillbilly humor they were meant to evoke. The G's are dropped, and the

mud is thrown. In his 1996 reelection bid against the future governor

Steve Beshear, McConnell's ads played off his opponent's last name. One

warned voters in a Kentucky drawl not to get "BeSheared." In another,

the voiceover declared "Old Beshear's a state fair champion at fleecin'

taxpayers" who has taken thousands of dollars "from them foreign agents

and lobbyists." The ads all featured sheep being sheared.

McConnell only played dumb on TV. Behind the scenes, he engineered

key victories in U.S. House races as he built the Republican Party in

Kentucky into a powerhouse. "He is the person primarily responsible for

making us a Republican state," says Al Cross, the veteran political

reporter and director of the University of Kentucky's

Institute for Rural Journalism and Community Issues.

When longtime and popular Democratic Sen. Wendell Ford decided not to

seek reelection in 1998, McConnell saw an opportunity to expand his

political empire. He'd been Kentucky's first Republican senator in 12

years. Now, as chairman of the National Republican Senatorial Committee

(NRSC), he tapped Rep. Jim Bunning, who had won six consecutive House

elections, to grab the other Senate seat.

"He was the chairman of the committee, and he was recruiting," says

longtime Bunning aide Jon Deuser. "They had a great working

relationship."

Bunning's opponent, Rep. Scotty Baesler, cut the profile of a

promising Democratic politician. He was known across the state as a

college basketball star for the University of Kentucky's iconic coach

Adolph Rupp. He'd worked as an attorney providing free services to the

poor before being elected mayor of Lexington.

Baesler had used his political capital to implement key support

programs for seniors and anti-drug initiatives targeting schoolchildren.

During the 1998 campaign, he helped push the Clinton administration

into providing more than

$19 million

to overhaul public housing in Lexington and provide job training

programs for the city's poor. He was the pragmatic liberal alternative

to McConnell.

Bunning had only one innate advantage over Baesler: He'd had the more

distinguished sporting career

as a Hall of Fame pitcher for the Philadelphia Phillies and Detroit

Tigers. He'd thrown a no-hitter and a perfect game. As a politician,

however, Bunning never got out of the minor leagues. He'd been an

unremarkable representative in the House, best known on Capitol Hill for

his acerbic blather and combative disposition.

McConnell, however, saw someone he could steer to victory. "He was

practically the campaign manager for Bunning in that race," says Dave

Hansen, a GOP campaign manager who served as political director of the

NRSC in the 1990s. The senator sent his top men to aid Bunning.

Kyle Simmons,

his chief of staff, took a leave of absence to become the Bunning

campaign coordinator. Tim Thomas, McConnell's field representative for

Western Kentucky, took personal leave to volunteer for the Senate

hopeful.

But the senator was more than just a careful stage manager. He was

the campaign's pivotal instigator. In August 1998, McConnell took the

stage at the annual Fancy Farm Picnic in Western Kentucky and delivered a

speech that would define the contentious race between Bunning and

Baesler.

The colorful, open-collar campaigning at

Fancy Farm,

a state-fair-sized festival, is a rarity in contemporary American

retail politics. Typically, stump speeches are choreographed for the

press, their audiences stacked with enthusiastic supporters. But at

Fancy Farm, those running for office are expected to tailor their speech

to the setting and let it rip under the ceiling fans. It's as much a

comedic roast as it is a political rally.

"It's kind of this throwback," Hansen explains. "Candidates get up

there, and they make the most outrageous comments to stir people up."

McConnell gave Bunning a clinic in his ruthless approach to

campaigning at the Fancy Farm event. The Republicans coordinated vicious

speeches targeting Baesler's status as a founding member of the Blue

Dogs -- a caucus of conservative House Democrats. Much to the chagrin of

progressives, Blue Dogs have since become a major force in Democratic

politics, but the group was still something of a novelty in the late

1990s, a fact that McConnell and Bunning exploited to comic effect.

McConnell slammed Baesler as a "blue chihuahua," who had "mistaken

Kentucky taxpayers for a fire hydrant" and who would serve as a "lap

dog" for President Bill Clinton. Bunning delivered a call-and-response

mockery with the festival's GOP audience.

"He would go through all these votes Baesler made and say, 'What do

y'all think about that?' And the crowd would shout, 'Bad doggy!'"

recalls Trey Grayson, an attorney and party activist who would later be

elected Kentucky's secretary of state.

The typically mild-mannered Baesler took the bait and responded with a

brutal stemwinder of a speech against Bunning, replete with outsized

hand gestures and ugly facial contortions. Although his rant played well

with the live audience, an angry man wildly waving his arms and

shouting in the August heat left a visual impression that was ripe for

McConnell's manipulation. As soon as Baesler's rant ended, McConnell was

eager to make sure his staff had caught it on tape.

"We filmed it," says Hansen, who was working for McConnell at the

time. "We put it to Wagner music, and it made one hell of an ad."

With Baesler's antics playing out in slow motion over music by Adolf

Hitler's favorite composer, McConnell moved the tone of American

political ads even lower than his landmark "Hound Dog" spot or the

Beshear sheep ads had.

"Mitch saw the video and thought he saw something. He showed it to

the Bunning folks," says Grayson. "Baesler looked crazy. He looked kinda

like Hitler."

"When I ran, he was the best help Jim ever had," Baesler says of

McConnell. "He got that ad running lookin' like I was a crazy man. I

thought that thing -- without question, he saw its value."

The race was not called until well after midnight, but Bunning

eventually emerged victorious by a little more than 6,000 votes. The

barrage of negative ads against Baesler not only worked, they

effectively ended his career in national politics. At 57, he was a

washout. Two years later, Baesler ran for his old House seat and lost to

a Republican by

18 points.

At least in Kentucky, McConnell has proven to be an incredibly

effective Democrat-vaporizing machine. He has ended the political

careers of everyone he has ever defeated, except Beshear, who was

elected governor in 2007, 11 years after losing to McConnell.

"When he took over a long time ago, Republicans weren't alive in

Kentucky," Baesler says. "Now everything's competitive. They've even had

a Republican governor. That wasn't the case until he got involved a

long time ago. He's the backbone of the whole thing. And I wish he

wasn't. If he hadn't been with Bunning, I woulda won."

McConnell had moved Kentucky Republicans a long way from Cooper's

passionate defense of Medicare. The defeat of the practical,

reform-minded Baesler had consequences for the state. In his 12 years as

a senator, Bunning's most significant legislative achievement consisted

of single-handedly blocking the extension of federal unemployment

benefits in 2010. His hardline stance eventually became a standard

negotiating position of the Republican Party, cold comfort to the more

than

10.7 percent of Kentuckians who were

officially out of work at the time.

Bunning's Senate career will be best remembered for his message to

those politicians who dared to provide aid to needy citizens: "

Tough shit."

PADUCAH'S FALLOUT

On their way to victory, McConnell had shared with Bunning a strategy

that he had long preached to his own campaign staffers. The senator had

adopted what he called his "west of Interstate 65 strategy," named for

the highway that splits the state from Louisville in the north down to

the Tennessee border. McConnell believed that his elections were won or

lost west of I-65. The far western counties were once a Democratic

stronghold, but the territory showed signs that it could be open to a

determined Republican.

"He basically told other parts of the state they weren't going to see

him as much from, say, the first of August till Election Day," a former

McConnell staffer recalls. "He primarily was going to focus west of

I-65. That's where he thought more gains could be made."

McCracken County, set along the banks of the Ohio River in Western

Kentucky, played a pivotal role in McConnell's expanding power and

influence. With its history of strong African-American leaders and

outspoken union membership, the county initially opposed him: When he

was first elected to the Senate in 1984 by a narrow margin, McConnell

lost McCracken by about 4,000 votes. It was a victory to even get that

close.

In his critical reelection fight against Sloane, however, McConnell

took the county by more than 1,500 votes, and his influence in the

region has grown ever since. McConnell now owns the west. Al Cross

credits Paducah, the McCracken county seat, and the surrounding area as

"the key to his success."

Sen.

Mitch McConnell (right) talked with USEC General Manager Howard Pulley

during a media tour of the Paducah Gaseous Diffusion Plant in the

plant's Central Control Facility on Aug. 12, 1999. (Photo by Billy

Suratt)

To capture Paducah, Cross says, McConnell had to court the uranium

enrichment plant's workers. "He understood from the get-go, you ... try

to take care of the biggest employer in the key town," Cross says. That

meant promising job security.

There were good reasons to be concerned about the Paducah plant's

survival. With the Cold War arms race giving way to the Three Mile

Island disaster in 1979 and new hope for arms treaties between the U.S.

and the Soviet Union, the Atomic City began to lose its luster. In 1980,

the Paducah plant employed about 1,940 workers in production

activities. Within five years, more than 650 of them were gone. In 1987,

a similar uranium enrichment facility in Oak Ridge, Tenn., was

shuttered, leaving Paducah and a third plant in Ohio as the only such

operations left over from the Manhattan Project. The technology was fast

becoming obsolete. Among the workers, rumors of the plant closing

became an ever-present part of the job.

If the Paducah plant were to close, it would have a devastating

effect on the local economy. Production only accounts for a fraction of

the plant's economic significance: Hundreds of guards, drivers and other

contract workers are employed at the plant, while restaurants,

homebuilders, and other establishments are all dependent on the business

that the plant's employees provide.

In 1990, McConnell offered an incumbent's solution by playing up his

ties to then-President George H.W. Bush and floating the idea of a new

state-of-the-art plant in Paducah. According to news accounts at the

time, Sloane was far less enthusiastic about nuclear power, citing

concerns about safety and hazardous waste. "That killed Sloane in that

campaign," the plant union's vice president, Jim Key, told HuffPost.

Paducah never got that new plant, but McConnell discovered a winning

strategy and continued to patch together new contracts and make-work

jobs, exploiting residents' fears over layoffs. The senator kept the

plant's doors open, but he did so at the expense of the workers' own

well-being. For decades, the plant's toxins had spread through the air

and into the ground, slowly killing its own workers and tainting the

surrounding area -- a fact McConnell ignored in Washington and in

Paducah.

Workers had breathed in plutonium-dipped dust, sloshed through areas

high in harsh chemicals, and got hazardous powders on their food and in

their teeth. They'd taken the poisons home with them on their clothes.

On site, workers had erected "Drum Mountain," a scrap heap that bled

contaminants into the soil. Lawyers and scientists would later deploy

"groundwater plume maps" to show how far the toxins had spread.

But the effects of the toxins were plain to see. As early as the

1970s, Fred Buckley's patriotic fervor had begun to dim. He no longer

completely trusted management. Although he moved up the plant's ranks,

from security guard to running control rooms, he suspected the work was

far more dangerous than his bosses had let on. When he welcomed his son

Michael at the plant in August 1973, he did so with a warning: Better

make sure the equipment isn't contaminated. Don't trust the company.

Trust yourself. "I tried to stress -- be sure to not take anybody else's

word for it," he recalls.

Buckley had seen his friend Joe Harding waste away to nothing. The

two had known each other since childhood, when their families had

adjoining corn and soybean farms in Tennessee and they walked to school

together along crop-lined roads. Valedictorian of his high school,

Harding took in a year of college while Buckley went off to war. But

when the two reunited at the plant, Buckley began to notice how the work

made Harding sick and the bosses hounded him for speculating about

possible radiation contamination. "They didn't give him the respect they

should have," Buckley says. "He did his job. Joe came to work after he

looked like a ghost."

Sores crept up Harding's legs and wouldn't heal. Fingernail-like

protrusions grew out of his elbows, wrists, palms and the soles of his

feet. The nails, he said in an audio diary, were "very, very painful."

He'd try to trim them, but they'd just grow back. His daughter, Martha

Alls, now 71, recalls watching his head shake violently from tremors

during Christmas and Thanksgiving dinners.

Harding, who would develop a fatal stomach cancer, knew he had

company among his fellow workers. He kept a record of 50 other workers

who were either dying or had died of cancer. An internal memo from the

plant revealed that management kept its own death list in secret.

In 1971, the plant fired a very sick Harding; he was denied workers'

compensation, pension, and health insurance. But Harding continued to

speak out against the plant and became a minor celebrity with the

anti-nuclear movement. He spent the night of his death in 1980, with his

body wasted away to barely more than bones and his skin wrinkled like a

walnut shell, giving a last interview to a Swedish media team who had

flown in. "I picked them up at the Holiday Inn," Alls says of the

foreign reporters. "They stayed with Daddy until midnight. I took them

back to the hotel. He died the next morning. I think it just wore him

out telling it all."

The year before McConnell was first elected to the Senate in 1984,

Clara Harding had her husband's body exhumed and his bones tested,

which, according to news accounts, revealed excessively high levels of

uranium. A decade later, a co-worker told The Boston Globe that Joe

Harding's exhumed body "was hotter than a firecracker."

Clara Harding kept up her husband's crusade, but it took a toll. She

had to sell her house and move into a duplex. "I think she wrote to

everyone in the government," Alls says. "I just felt like this was a

hopeless case. This was the government -- you don't mess with your

government." The federal government fought Harding's claim. According to

the Courier-Journal, the feds spent $1.5 million in legal fees to deny

her the $50,000 she sought in benefits.

McConnell's sole concern about the plant seems to have been

protecting it from layoffs and lawsuits. Midway through his first Senate

term, he came out in favor of economic sanctions against South Africa's

apartheid regime, but fought the ban on importing that country's

uranium. McConnell worried about the effect of fewer uranium shipments

on jobs back in Paducah. In 1988, he voted against an amendment that

would have made Department of Energy nuclear subcontractors liable for

accidents caused by intentional negligence or misconduct at plants like

Paducah.

McConnell's opposition to trial lawyers became his justification for

inaction on worker health. After coming out against another provision

aimed at assisting workers in high-risk jobs, he complained that the

bill would simply "stimulate personal injury and worker compensation

litigation on a scale far beyond our present imagination."

Back in Paducah, however, the litigation was just about to begin.

In the late '80s, wells near the plant were showing signs of possible

contamination. Ronald Lamb helped run a mechanic shop on his family's

old farmland a few miles from the plant. He and his father and mother

all drank from the same well and started getting sick. "We thought we

were dying," Lamb told HuffPost. "I lost the hair on my arms. It looked

like I had chemo."

On Aug. 12, 1988, government officials contacted 10 households with

an ominous directive: Stop drinking and bathing in the water from their

wells. The Department of Energy began sealing off wells near the plant

and re-routing the water supply for roughly 100 residences.

Lamb says he repeatedly wrote letters to his local elected officials,

including McConnell, but didn't get much more than a form letter in

response. "They felt your pain but felt like you were being taken care

of," Lamb recalls.

Lamb didn't think so and spoke up around the country, including two

trips to Washington in the early '90s on his own dime. He and his family

also filed a lawsuit. Even though that case was unsuccessful, it led to

a January 1997 class-action lawsuit with Lamb and dozens of other area

residents that argued the plant had rendered their properties

essentially worthless. The complaint alleged that "massive" discharges

of radioactive materials and heavy metals had spread to their land,

"causing and threatening severe property damage and health problems."

The complaint further alleged that the flow of hazardous waste continued

unabated. That case was settled in 2010 for an undisclosed amount.

Ruby English, a West Paducah resident whose well was shut off, says

her husband Ray had also written to McConnell without success. English

had thyroid and colon cancer. Ray worked in the nearby wildlife refuge

bordering the plant, she says, and he'd come home with stories about

seeing the creek water turn purple and yellow. He'd drink from the well

and wash in the creek. He died a few years ago, his immune system a

wreck. "The damage is done. I feel sorry for the workers the most,"

English says. "They're right in the middle of it. ... It's pathetic, it

really is."

"Once full of aquatic life," the court complaint filed on behalf of

residents stated, "the Little Bayou Creek is now void of any meaningful

plant or animal life." A

pair of deer were found

near the plant in the early '90s with trace amounts of plutonium in

their systems, according to the Associated Press. A 1990 Department of

Energy inspection report noted that hazardous contamination had spread

to rabbits, squirrels and apple trees.

The inspection highlighted management deficiencies and evidence of

contamination at the Paducah plant. In multiple areas, management

acknowledged the plant lacked the tools to measure such contamination or

had not put adequate safeguards in place. Four years later, the

Environmental Protection Agency declared the facility a Superfund site,

adding it to the agency's official list of ecological cleanup

priorities.

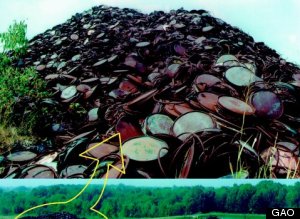

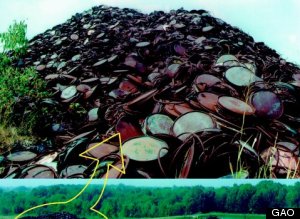

The Paducah plant's hazardous "Drum Mountain." (Photo from a GAO report)

Michael Buckley remembers the very room where they had held worker

meetings had to be cordoned off; the room was found to be full of

contaminants. Drum Mountain, he says, was no secret. "I didn't consider

it a joke," he remembers. "Everybody knew the residue in the barrels was

contaminated. You know that runoff's gonna get into the underground

water."

The workers had little control over the mess and lacked suitable

protections. "The essential problems were created in the haste to build

nuclear weapons," says Terry Lash, director of the Department of

Energy's Office of Nuclear Energy during the 1990s. "Because of the

threat to the existence of the country, they just didn't worry about the

long term."

McConnell and other Kentucky officials were intimately familiar with

the plant's problems. Tim Thomas, who worked on McConnell's staff as a

field representative for Western Kentucky starting in 1997, told

HuffPost that the senator's office and the Department of Energy had

discussions "on a regular basis."

McConnell and his staff toured the facility every few years and knew

about the contaminated water supply and the mountain of leaking storage

containers. McConnell also knew the name of Joe Harding. "I had heard of

the widow," Thomas says. "We had heard of Joe Harding. We didn't know

if this was an isolated incident or what. We were not in an

investigative position."

Mark Donham, 60, served as chairman of the Paducah Citizens Advisory

Board, which was tasked with watchdogging safety issues and making

recommendations to the Department of Energy about the cleanup. He

doesn't recall Thomas or any other representatives from McConnell's

office taking a big interest or even attending the board's public

meetings detailing the contamination spread.

Meanwhile, the plant's own community relations plan in January 1998

noted that the number of possible hazardous waste zones had soared to

208. Despite all the concerns, Donham says, "McConnell never stood up

and lobbied for an investigation."

When The Huffington Post asked McConnell at his weekly Senate press

conference on the Hill in June about his handling of the hazardous waste

issue, the senator brushed it aside. "That's of course a parochial

question," he said. "I'll be happy to address it if you'll check with

the office." His office did not respond to follow-up questions or

multiple requests for an interview with the senator.

It was not until The Washington Post reported in August 1999 -- 19

years after Harding's death and five years after the Superfund listing

-- that thousands of plant workers "were unwittingly exposed to

plutonium and other highly radioactive metals," turning the plant's

problems into a national scandal, that McConnell finally sprang into

action. He called for hearings into the contamination outside the plant

and rushed to Paducah for a tour of the facility.

McConnell and Bunning requested a Government Accountability Office report on the situation at the plant, but the agency

returned a scathing indictment

of the senators' own inaction. Since 1993, McConnell had served on the

Senate Appropriations Committee -- the panel responsible for the

government's final funding decisions -- but according to the GAO, the

Department of Energy hadn't been given the money it had requested to

clean up the Paducah site.

"The funding available for cleanup had been much less than requested

[by DOE]," the April 2000 report reads. "Cleanup at the site, including

the removal of contaminated scrap metal and low-level waste disposal,

was delayed because of funding limitations."

All told, there were roughly 496,000 tons of depleted uranium in

storage, according to the GAO, along with 1 million cubic feet of

"uncharacterized waste." Drum Mountain had swollen to 8,000 tons of

life-endangering scrap and stood nearly 40 feet tall. The feds suggested

that the plant, so utterly compromised, could become its own

spontaneous threat. "Some of this waste and scrap material poses a risk

of an uncontrolled nuclear reaction that could threaten worker safety,"

the report reads.

With a wave of press coverage focused on the Paducah plant, McConnell

did something that few in Washington would expect from the fierce

Obamacare opponent: He worked to pass what amounted to a new entitlement

that allowed plant workers over age 50 access to free body scans and

free health care. The program also provided $150,000 lump sum payments

to workers who developed cancers or other illnesses from radiation

exposures, and up to $250,000 in compensation for medical problems

caused by other toxins. Spouses and children were also eligible for the

program, which cost the federal government more than

$9.5 billion.

But the legislation was not a high priority on Capitol Hill. When the

bill stalled, Bill Richardson, then President Clinton's energy

secretary, credits McConnell with pushing it through. "I remember the

bill was in trouble," Richardson told HuffPost. "There was some

last-minute shenanigans, and McConnell got it done."

At least to Richardson, McConnell claimed to have worried about

safety at the plant. "McConnell talked to me about this issue,"

Richardson says. "He was pretty outraged, but he basically said that he

had been trying to work [on this] and I was the first secretary to

listen."

After the bill became law and the entitlement was put in place in

2001, McConnell and his wife, Elaine Chao, who was President George W.

Bush's labor secretary at the time, flew to Paducah and awarded the

first $150,000 check and a folded American flag to Harding's widow. The

money was nowhere near enough to cover the extent of his medical bills.

"He didn't get anything compared to what he was supposed to," his

daughter Alls, who says she's a McConnell supporter, told HuffPost. She

added that the ceremony "meant everything to Mother. ... It was

recognition that Daddy had done good." Residents who drank from the

poisoned wells, like Lamb and English, weren't covered by the

entitlement.

But the program was enormously popular in Kentucky, and with good

reason. Workers who had seen nothing for decades were suddenly receiving

payments. Thousands of others were being screened, and many lives were

saved. The free checkups caught cancers and heart conditions.

The exams identified a few suspicious nodules in Michael Buckley's

lungs. "I want to definitely keep track of the problems and make sure

they don't get any larger," he says.

Years later, during his 2008 reelection campaign, McConnell was still

championing the compensation bill in a TV ad that featured Michael's

father, Fred, praising the senator for helping out Paducah's workers.

"Without a doubt, Senator McConnell has saved people's lives," Fred

Buckley told viewers. The ad ended with another worker declaring that

the senator "cares for the working man."

McConnell had spun a political liability into gold, going from

potential goat to savior. He flooded the media market in Western

Kentucky with that ad. "They ran that thing every night it seemed like

to me for two years," Fred Buckley recalls.

Cleanup is still slow in coming. Outside Big Bayou Creek, which flows

into the Ohio River, the Department of Energy has posted a sign that

warns of toxic sediment. "Use of this waterway for drinking, swimming or

other forms of recreation may expose you to contamination," it states.

In 2008, the senator thumped his Democratic opponent by more than 4,000 votes in McCracken County.

MCCONNELL'S SAFETY NET

In Paducah, old men waited years with cancerous growths before they

were treated. In Appalachia, men with rotting teeth give up waiting and

yank them out with pliers. In the southwest part of the state, prenatal

care for some expectant mothers is an emergency room visit after their

water breaks. In central Kentucky, a woman must live five months with a

numb arm before seeing a nurse at a free clinic 45 miles from home.

Kentucky doesn't have so much a safety net as a painful waiting list

-- a very, very long one. More than 17 percent of its citizens go

without health insurance of any kind,

even as the state's high poverty rate results in more than 880,000

Medicaid patients. Only about 43 percent of the state buys health

insurance from the private sector.

The public health results are what you might expect: terrible. The

state has the seventh-highest obesity rate in the nation and,

predictably, the eighth-shortest life expectancy. Kentucky babies start

with disadvantages from their first cry: The number of premature births

in the state has increased over the past decade, while the number of

babies born addicted to drugs jumped by

nearly 1,100 percent

between 2001 and 2011. Certain counties have infant mortality rates

higher than those of "third world countries," according to a March 2013

report from the Kentucky Department of Public Health.

To try to address the needs of Kentucky residents, health care

providers in the state have been forced to get creative. In Elkton, the

Helping Hands Health Clinic is supported by twice-a-week bingo games put

on by the staff, while in Danville, the Hope Clinic operates out of an

old bank and serves six counties. Last July, a mobile clinic set up a

triage on fairgrounds in Wise County, Virginia, which served many

Kentucky residents who crossed over the state line. Stan Brock, the

clinic's founder, says that in a little more than two days, they saw

1,453 dental patients and pulled 3,467 teeth. "It filled several

buckets," he recalls.

For years, McConnell responded to Kentucky's poverty and health care

crises by directing millions of dollars in federal earmarks to various

projects in the state, constructing what has amounted to a lottery

system. To get help, the plight of Kentuckians did not have to rise to a

national scandal like the Paducah plant's contaminated workers. Nor did

it require the tint of a conservative cause. They just had to be very

lucky. (Nobody has emphasized just how lucky more than the senator

himself. McConnell has greeted the recipients of his earmarked funds

like winners of the Powerball jackpot, complete with giant novelty

checks.)

Earmarks have political benefits, and McConnell made a point of

visiting remote counties to tout the federal money he had secured for

his constituents.

"I hate to call it passing out checks, but you know that's kind of

what it amounts to," says David Cross, who served as chairman of the

Clinton County Republican Party until 2012. Cross remains a

McConnell-supporting Republican, and still lives in Clinton County,

which has a population of about 10,000 on the state's southern border.

Cross says McConnell would visit Clinton "when there was some aspect of

the federal government involved locally and Senator McConnell was

involved and he wanted the local community to know he was involved."

McConnell was one of hundreds of politicians who benefited from

making this kind of selective disclosure, since earmarks were

essentially anonymous under congressional procedures for decades. New

rules in 2008 required members of Congress to disclose their funding

requests, and the practice was banned outright in 2011. A Huffington

Post review of three years' worth of public earmarks, from 2008 through

2010, shows that McConnell orchestrated the delivery of nearly half a

billion dollars in federal funds, with a pronounced emphasis on projects

in his home state. If earmarks coordinated with presidential budgets

are included, the figure swells to $1.5 billion.

Earmarks are no longer part of McConnell's political toolkit, but the

senator is still campaigning on his pork-barrel legacy. Just days after

Alison Lundergan Grimes formally jumped into the Senate race, he was

already reminding voters of the federal benefits he has steered to

Kentucky, and ridiculing Grimes' ability to bring home the bacon as a

backbencher.

"Kentucky would lose dramatically by trading in a leader of one of the two parties in the Senate for a rookie,"

McConnell told reporters on July 3.

"Kentucky is in an extraordinary position of influence as a result of

their confidence in me over the years. ... Do we really want to lose the

influence?"

The biggest chunk of McConnell's earmarks were devoted to defense

spending, but they financed an astonishing variety of projects,

including at least $21.9 million on civilian health efforts and $24

million for a "medical/dental clinic" at the Army's Fort Campbell.

McConnell directed money to everything from mobile health screenings

to lab upgrades for stem cell research into heart failure. One earmark

funneled money to a University of Louisville scientist for

groundbreaking research into aging, with treatment implications for

Alzheimer's and even space travel.

Indeed, the state's public universities have been big benefactors of

the senator's earmarks. In the decade before the earmark ban, McConnell

bestowed approximately $140 million on the University of Kentucky,

according to Bill Schweri, the university's director of federal

relations. Much of the McConnell largess went to new building

construction and steady research support.

Schweri met regularly with McConnell's staff, becoming intimately

familiar with what the senator would approve. McConnell's staff had the

same basic questions for every pitch: How will this help Kentucky? How

will this keep University of Kentucky alums from fleeing the state? "He

wanted to see the university be an economic driver in the state,"

Schweri explains.

Using a public university to drive the state's economy, much less

providing public health care, would be anathema to members of the tea

party. At least nationally, the Senate minority leader isn't so generous

or noble. McConnell has, almost as a matter of routine, favored

corporate subsidies and tax cuts for the wealthy over safety net support

for Americans living in poverty. Nearly every social support program

can count on McConnell's opposition, from home heating assistance to

allowing states to access cheaper medications.

Children receive no special exemption from McConnell's tough love at

the federal level. He has sought to prevent disabled children of legal

immigrants from receiving benefits and has been a fierce opponent of the

Children's Health Insurance Program, which provides medical coverage

for families who make too much to qualify for Medicaid but can't afford

private insurance. It is no shock that his opposition to Obamacare has

been unwavering, all the way down to Medicaid expansion in his own

state, which will give

more than 350,000 Kentuckians access to the program.

But at least in Kentucky, there is what might be called the McConnell

option. Some of his federal appropriations went to health care services

for the state's most vulnerable citizens. And unlike Obamacare, his

earmarks frequently provided direct government services without a

private-sector intermediary.

In the 2005 and 2008 federal budgets, McConnell and his staff

recognized the rotting teeth and premature birth problems in their

state, and funded a program whose research saw a linkage between the

two. The University of Kentucky received a total of $1.78 million for

the program -- a drop in the bucket, but, Schweri says, an easy sell.

"Staff picked up on it right away," he recalls. "Senator McConnell

has really, really good staffers. They are very knowledgeable. It never

ceases to amaze me how clued in they are to the state of Kentucky."

The earmark funding trickled down to the Baptist Women's Clinic's

pilot prenatal care program, known as "CenteringPregnancy," which

targeted at-risk, soon-to-be moms. Along with providing sonograms and

routine care, nurses and midwives moderated group sessions that went

beyond breathing exercises and swaddling techniques. They found room to

address what so much of Kentucky's social services could not.

A couple attending a group session at CenteringPregnancy in late February.

The expectant moms talked about not having a place to live, worries

about completing high school, and living under the boot of abusive men.

Some women confessed they couldn't afford transportation and had to walk

to the sessions.

"It will be the heat of the summer, and you will have moms that are

walking," says LeAnn Langston, a registered nurse and a nurse manager

with the clinic. "We've had women pushing strollers in the heat of the

summer." After bonding with each other at the sessions, groups formed

carpools.

In 2006, CenteringPregnancy's first year, 370 women participated,

almost all of them young and on Medicaid. The program's popularity

ensured a significant impact locally, but like many of McConnell's other

health solutions, it was all but irrelevant statewide.

The earmark provided for an examination room as well as a dentist and

a hygienist on site to offer screenings and cleanings at no charge to

the mothers. Oral infections can complicate a pregnancy and have an

impact on birth weight. Some of the women, Langston recalls, had never

been taught how to use a toothbrush. "A lot of it was the culture --

‘Everyone in my family has false teeth,'" Langston explains. "They would

show up in the ER if they had a toothache. They really didn't

acknowledge their mouth unless there was pain."

The clinic dentist flushed diseased gums, excavated years of

calcified plaque and uprooted necklaces of dead teeth. Full-mouth

extractions, Langston says, were not rare. Neither was evidence of drug

use. After the clinic put in place random drug testing and ramped up

counseling, Langston says, nearly 90 percent of the women who tested

positive on the initial visit were drug-free by the time they were ready

to deliver their babies.

The women needed all the help they could get. For many low-income

mothers in Kentucky, Medicaid covers at most the first two months after

they give birth. If they have drug problems, bed space at rehab

facilities is limited across the state. Just traveling to these places

can be a barrier, says Dr. Ruth Ann Shepherd, the director of the

Division of Maternal and Child Health in the state's Department for

Public Health. "I don't know that there is ever going to be enough

treatment facilities," she adds.

Lack of space isn't the only problem. After weeks of effort, Langston

and her team recently secured one of her moms-to-be a spot in a detox

facility roughly three hours away in Lexington. Her detox lasted five

days and ended with the promise of outpatient counseling, the woman, 31,

told HuffPost.

She had been soothing her anxieties with illegal prescription drugs,

methadone and, on the rare occasion, she says, crystal meth. She didn't

see a single therapist at detox. It took her 48 hours to relapse.

"I felt like I needed it," she says. "I had a panic attack as soon as

I got home. I'm a self-medicator. That's just where I go." It's been

more than a month and she's still waiting for the outpatient care.

Today, the drug testing and the CenteringPregnancy program continue

at Langston's clinic. But the funding from McConnell's earmark dried up

in 2009, and without it the on-site dental clinic had to close.

Similarly, high blood pressure and diabetes are huge problems across

the state. In the 2009 and 2010 federal budgets, McConnell earmarked

close to $3 million to fund heart health classes that would educate

residents in the state's rural areas about how to eat better and

exercise. Organized by the University of Kentucky, the class curriculum

-- with its eat-your-vegetables philosophy -- would not have been out of

place at one of Michelle Obama's Let's Move events.

Instead of getting kids interested in exercise, however, these

classes aimed to persuade adults to stop eating only canned vegetables

and to replace soda with water. Debra Moser, a nurse and professor with

the University of Kentucky who designed the project and participated in

some of the class work, recalls people saying their parents had died

from heart attacks and they were just going to die of one, too. Others

said they drank soda because coal mining had contaminated their wells.

The program couldn't address the poisonous wells. But it could at

least highlight alternatives in the Kroger aisles. Moser says about

1,400 residents enrolled in the classes; 60 percent didn't have a

primary physician. For those who stuck with it and continued to be

monitored by health care providers after the classes ended, there were

across-the-board reductions in the risk factors for heart disease.

Along with the exercise tips and self-sufficiency lessons, the class

instructors passed on referrals to places like the Hope Clinic in

Danville, where low-income and no-income residents could get free health

care. Hope receives only enough funding to operate part-time during the

week and has just three rooms, including one with a recliner for

patients with mobility issues or those who are so obese that they can't

lift themselves up onto the examination table.

Late February brought two new patients who had gone without health

care for years, recalls Terry Casey, a nurse practitioner at Hope. Both

had stroke-level blood pressures. Casey says she obtained medications

right away from a local pharmacy and promptly sent off lab work, but

their conditions were already grave. Within two weeks, one had suffered a

stroke while the other had a heart attack.

Casey, whose clinic receives no federal funding, thinks the heart

health classes are a small Band-Aid for a much larger problem. And she

was surprised that McConnell had anything to do with them. "Every day I

see people who come through here that are in such terrible shape without

resources that, from my perspective, what I see is people like

McConnell working against expanded health care coverage and they get

involved in the politics and they don't pay attention to what's going on

on the ground level," she says.

Shelia Calladine, 63, and her dog, outside the school bus in which she lives.

In nearby Lincoln County, down a two-lane road hemmed in late

February by dry yellow pastures and lonely houses gray with rot, Shelia

Calladine, 63, is living out of a school bus painted white and parked on

a Baptist association's property, the keys and electricity courtesy of a

man she calls "Brother Gary." The bus seats have been ripped out and

replaced with dollar-store clutter. The centerpiece of a small table is

an empty pale blue pill organizer sitting on top of a plastic Cash

Express cup.

Calladine says she was only allowed to move into this

shelter-on-wheels if she agreed to marry her boyfriend. That was the

deal Gary had made with the couple. The marriage, Calladine says, was a

mistake. "I shouldn't have done that," she says. "I don't feel forced

but pushed. Not forced but pushed."

As a cold, persistent rain fell outside and her skinny dog yipped at

the barren farm and empty lots, Calladine spoke about growing up as a

restaurant manager's daughter who began waitressing at age 9 and never

finished high school. She spent decades behind dimly lit bars and

truck-stop cash registers. When she realized that she couldn't see the

poker machines from the bar, a doctor told her she had diabetes. She

didn't have health insurance. If she ran out of insulin before payday,

she had to hope her body wouldn't miss it. Sometimes she woke up in

hospital beds.

While she was working at a truck stop in Livingston, a co-worker

found her naked on a bed in the motel where she lived. She'd fallen into

a diabetic coma.

McConnell's earmarks never shone their short-term hope on Calladine.

Somewhere, maybe a county away, they found some other down-on-their-luck

souls and taught them about turkey bacon or pulled a dead tooth from

their rotting gums. But the senator never chose what his state truly

required: comprehensive solutions to, instead of temporary patches over,

the gaping holes in Kentucky's health care system.

Obamacare has its own shortcomings for Kentucky. It will not address

the chronic shortage of doctors in rural areas or the lack of doctors

who accept poor patients. But it will at least grapple with the

statewide crisis in accessing health insurance.

After returning to Lincoln County and finding the Hope Clinic,

Calladine says, she has been able to get a handle on her diabetes and a

recently discovered thyroid condition. The rest of her care must wait,

however -- even emergencies.

Three weeks earlier, Calladine fell and fractured her ankle. But the

emergency room is only free with a referral from the clinic, and her

next appointment at Hope wasn't for two days. So she had no choice but

to wait, sit out the pain and watch her ankle swell. "If it got any

fatter, it felt like it was going to bust," she said.

THE LEGACY HE SOUGHT

Early in McConnell's first campaign for Jefferson County

judge-executive in '77, staffer Charlie Musson remembers calling

businesses and asking if his candidate could stand outside their

storefront and do some politicking. On the way to one of those first

campaign stops, he could see McConnell stewing in the backseat of their

car.

"The whole drive out you could tell he's getting anxious," Musson says.

Finally, McConnell couldn't help but speak up. Maybe they could turn

the car around and just go back home. "How do I do this?" he asked.

McConnell was actually good with young voters and had impressed

Musson with the way he took the time to talk politics over Cokes with

his high-school-aged volunteers. But even with this first campaign, the

35-year-old McConnell understood his true value. "Can I go back and make

fundraising calls?" he offered from the back seat.

Before the race, when he was teaching political science at the

University of Louisville, McConnell had explained to his class what

built a political party. He'd written on the blackboard three words:

"Money, money, money." Although he would churn out position papers, he

told Louisville Today after his victory that "issues, unfortunately,

usually are kind of peripheral to winning a campaign."

McConnell eventually carried that philosophy into the Senate. It's what people note most vividly about his tenure.

The day after winning his first reelection contest in 1990, he was

already using the occasion to solicit funds for his next campaign.

Former Louisville Mayor Wilson Wyatt told Louisville Magazine about a

lawyer at his firm inviting Wyatt to the event. "He asked me if I cared

to join him and a few others for lunch with Senator McConnell, to

celebrate. Then he said I'd need to bring along a check for $2,000,

because the senator was already raising money for 1996," Wyatt told the

magazine in 1995. "He's serious."

Alan Simpson, the now-retired Republican senator from Wyoming,

recalled to the Lexington Herald-Leader in 2006 that when McConnell

asked for money, "his eyes would shine like diamonds. He obviously loved

it." A former aide to Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.) and Christian

Coalition lobbyist remarked in the same article that fundraising is the

senator's "great love above everything else. ... His fundraising is like

a corporation, a booming, full-time business."

In the mid '90s, McConnell was tapped to run the GOP's Senate

business as chairman of the National Republican Senatorial Committee.

The job meant targeting winnable races, helping to discover promising

candidates and building a war chest that could put on-the-bubble

contests in play. All the spreadsheets and the strategy sessions showed

McConnell had a real chance at a Senate takeover.

Democrats were defending more seats than Republicans in 1998 --

Arkansas, Nevada, Ohio and both Carolinas were all major GOP targets. It

was six years into Bill Clinton's presidency -- a time when the