Irish Slavery

by

James F. Cavanaugh

junglejim@btl.net

There are a great many K/Cavanaughs in North America who trace

their ancestry back to a Charles Cavanaugh, who arrived in Virginia,

with a brother or cousin named Philemon Cavanagh (Felim or Phelim), on

or about 1700. Their descendants most often spell their name with a C,

although a variety of both C and K spellings are found, even within the

same immediate family.

They were originally concentrated in the

Southeastern United States, particularly Virginia, North Carolina and

Georgia, but now spread to everywhere. Although long standing family

traditions trace Charles and Philemon of 1700 arrival back to Colonel

Charles Cavanaugh of Carrickduff and Clonmullen, (the son of Sir Morgan

Cavanagh, the son of Donnal Spanaigh Cavanagh), a recorded link still

evades researchers.

A possible link, however, was found in Barbados, where the birth

of a Charles Cavanaugh, son of Charles Cavanaugh, was registered there

in January 1679. At the same time, another Cavanagh was registered as

inbound on a ship to Barbados from Liverpool. And further complicating

the entry is the same registry records the death of a Charles Cavanaugh,

son of Charles at the same time. So the questions: was the dead Charles

the new born baby; or perhaps the father of the baby; or maybe the

inbound Cavanagh who may have died on the trip to Barbados, with his

death recorded upon arrival; or another Charles; or�.?

These questions are still unanswered, but a more intriguing

question is what were the Cavanaughs doing in Barbados in the first

place? The answer takes us down a revolting path wandering through one

of the most insensitive and savage episodes in history, where the greed

and avarice of the English monarchy systematically planned the genocide

of the Irish, for commercial profit, and executed a continuing campaign

to destroy all traces of Irish social, cultural and religious being. As

the topic was politically sensitive, little has been written about this

attempted genocide of the Irish, and what has been written has been

camouflaged because it is an ugly and painfully brutal story. But the

story should be told.

Transportation and Banishment

If Queen Elizabeth I had lived in the 20th Century. she would

have been viewed with the same horror as Hitler and Stalin. Her policy

of Irish genocide was pursued with such evil zest it boggles the mind of

modern men. But Elizabeth was only setting the stage for the even more

savage program that was to follow her, directed specifically to

exterminate the Irish. James II and Charles I continued Elizabeth�s

campaign, but Cromwell almost perfected it. Few people in modern

so-called �civilized history� can match the horrors of Cromwell in

Ireland. It is amazing what one man can do to his fellow man under the

banner that God sanctions his actions!

During the reign of Elizabeth I, English privateers captured 300

African Negroes, sold them as slaves, and initiated the English slave

trade. Slavery was, of course, an old established commerce dating back

into earliest history. Julius Caesar brought over a million slaves from

defeated armies back to Rome. By the 16th century, the Arabs were the

most active, generally capturing native peoples, not just Africans,

marching them to a seaport and selling them to ship owners. Dutch,

Portuguese and Spanish ships were originally the most active, supplying

slaves to the Spanish colonies in America. It was not a big business in

the beginning, but a very profitable one, and ship owners were primarily

interested only in profits. The morality of selling human beings was

never a factor to them.

After the Battle of Kinsale at the beginning of the 17th century,

the English were faced with a problem of some 30,000 military

prisoners, which they solved by creating an official policy of

banishment. Other Irish leaders had voluntarily exiled to the continent,

in fact, the Battle of Kinsale marked the beginning of the so-called

�Wild Geese�, those Irish banished from their homeland. Banishment,

however, did not solve the problem entirely, so James II encouraged

selling the Irish as slaves to planters and settlers in the New World

colonies. The first Irish slaves were sold to a settlement on the Amazon

River In South America in 1612. It would probably be more accurate to

say that the first �recorded� sale of Irish slaves was in 1612, because

the English, who were noted for their meticulous record keeping, simply

did not keep track of things Irish, whether it be goods or people,

unless such was being shipped to England. The disappearance of a few

hundred or a few thousand Irish was not a cause for alarm, but rather

for rejoicing. Who cared what their names were anyway, they were gone.

Almost as soon as settlers landed in America, English privateers

showed up with a good load of slaves to sell. The first load of African

slaves brought to Virginia arrived at Jamestown in 1619. English

shippers, with royal encouragement, partnered with the Dutch to try and

corner the slave market to the exclusion of the Spanish and Portuguese.

The demand was greatest in the Spanish occupied areas of Central and

South America, but the settlement of North America moved steadily ahead,

and the demand for slave labor grew.

The Proclamation of 1625 ordered that Irish political prisoners

be transported overseas and sold as laborers to English planters, who

were settling the islands of the West Indies, officially establishing a

policy that was to continue for two centuries. In 1629 a large group of

Irish men and women were sent to Guiana, and by 1632, Irish were the

main slaves sold to Antigua and Montserrat in the West Indies. By 1637 a

census showed that 69% of the total population of Montserrat were Irish

slaves, which records show was a cause of concern to the English

planters. But there were not enough political prisoners to supply the

demand, so every petty infraction carried a sentence of transporting,

and slaver gangs combed the country sides to kidnap enough people to

fill out their quotas.

Although African Negroes were better suited to work in the

semi-tropical climates of the Caribbean, they had to be purchased, while

the Irish were free for the catching, so to speak. It is not surprising

that Ireland became the biggest source of livestock for the English

slave trade.

The Confederation War broke out in Kilkenny in 1641, as the Irish

attempted to throw out the English yet again, something that seem to

happen at least once every generation. Sir Morgan Cavanaugh of

Clonmullen, one of the leaders, was killed during a battle in 1646, and

his two sons, Daniel and Charles (later Colonel Charles) continued with

the struggle until the uprising was crushed by Cromwell in 1649. It is

recorded that Daniel and other Carlow Kavanaghs exiled themselves to

Spain, where their descendants are still found today, concentrated in

the northwestern corner of that country. Young Charles, who married Mary

Kavanagh, daughter of Brian Kavanagh of Borris, was either exiled to

Nantes, France, or transported to Barbados� or both. Although we haven�t

found a record of him in a military life in France, it is known that

the crown of Leinster and other regal paraphernalia associated with the

Kingship of Leinster was brought to France, where it was on display in

Bordeaux, just south of Nantes, until the French Revolution in 1794. As

Daniel and Charles were the heirs to the Leinster kingship, one of them

undoubtedly brought these royal artifacts to Bordeaux.

In the 12 year period during and following the Confederation

revolt, from 1641 to 1652, over 550,000 Irish were killed by the English

and 300,000 were sold as slaves, as the Irish population of Ireland

fell from 1,466,000 to 616,000. Banished soldiers were not allowed to

take their wives and children with them, and naturally, the same for

those sold as slaves. The result was a growing population of homeless

women and children, who being a public nuisance, were likewise rounded

up and sold. But the worse was yet to come.

In 1649, Cromwell landed in Ireland and attacked Drogheda,

slaughtering some 30,000 Irish living in the city. Cromwell reported: �I

do not think 30 of their whole number escaped with their lives. Those

that did are in safe custody in the Barbados.� A few months later, in

1650, 25,000 Irish were sold to planters in St. Kitt. During the 1650s

decade of Cromwell�s Reign of Terror, over 100,000 Irish children,

generally from 10 to 14 years old, were taken from Catholic parents and

sold as slaves in the West Indies, Virginia and New England.

In fact,

more Irish were sold as slaves to the American colonies and plantations

from 1651 to 1660 than the total existing �free� population of the

Americas!

But all did not go smoothly with Cromwell�s extermination plan,

as Irish slaves revolted in Barbados in 1649. They were hanged, drawn

and quartered and their heads were put on pikes, prominently displayed

around Bridgetown as a warning to others. Cromwell then fought two quick

wars against the Dutch in 1651, and thereafter monopolized the slave

trade. Four years later he seized Jamaica from

Spain, which then became the center of the English slave trade in the Caribbean.

On 14 August 1652, Cromwell began his Ethnic Cleansing of

Ireland, ordering that the Irish were to be transported overseas,

starting with 12,000 Irish prisoners sold to Barbados. The infamous

�Connaught or Hell� proclamation was issued on 1 May 1654, where all

Irish were ordered to be removed from their lands and relocated west of

the Shannon or be transported to the West Indies. Those who have been to

County Clare, a land of barren rock will understand what an impossible

position such an order placed the Irish. A local sheep owner claimed

that Clare had the tallest sheep in the world, standing some 7 feet at

the withers, because in order to live, there was so little food, they

had to graze at 40 miles per hour. With no place to go and stay alive,

the Irish were slow to respond. This was an embarrassing problem as

Cromwell had financed his Irish expeditions through business investors,

who were promised Irish estates as dividends, and his soldiers were

promised freehold land in exchange for their services. To speed up the

relocation process, a reinforcing law was passed on 26 June 1657

stating: �Those who fail to transplant themselves into Connaught or Co

Clare within six months� Shall be attained of high treason� are to be

sent into America or some other parts beyond the seas� those banished

who return are to suffer the pains of death as felons by virtue of this

act, without benefit of Clergy.�

Although it was not a crime to kill any Irish, and soldiers were

encouraged to do so, the slave trade proved too profitable to kill off

the source of the product. Privateers and chartered shippers sent gangs

out with quotas to fill, and in their zest as they scoured the

countryside, they inadvertently kidnapped a number of English too. On

March 25, 1659, a petition of 72 Englishmen was received in London,

claiming they were illegally �now in slavery in the Barbados�' . The

petition also claimed that "7,000-8,000 Scots taken prisoner at the

battle of Worcester in 1651 were sold to the British plantations in the

New World,� and that �200 Frenchmen had been kidnapped, concealed and

sold in Barbados for 900 pounds of cotton each."

Subsequently some 52,000 Irish, mostly women and sturdy boys and

girls, were sold to Barbados and Virginia alone. Another 30,000 Irish

men and women were taken prisoners and ordered transported and sold as

slaves. In 1656, Cromwell�s Council of State ordered that 1000 Irish

girls and 1000 Irish boys be rounded up and taken to Jamaica to be sold

as slaves to English planters. As horrendous as these numbers sound, it

only reflects a small part of the evil program, as most of the slaving

activity was not recorded. There were no tears shed amongst the Irish

when Cromwell died in 1660.

The Irish welcomed the restoration of the monarchy, with Charles

II duly crowned, but it was a hollow expectation. After reviewing the

profitability of the slave trade, Charles II chartered the Company of

Royal Adventurers in 1662, which later became the Royal African Company.

The Royal Family, including Charles II, the Queen Dowager and the Duke

of York, then contracted to supply at least 3000 slaves annually to

their chartered company. They far exceeded their quotas.

There are records of Irish sold as slaves in 1664 to the French

on St. Bartholomew, and English ships which made a stop in Ireland

enroute to the Americas, typically had a cargo of Irish to sell on into

the 18th century.

Few people today realize that from 1600 to 1699, far more Irish were sold as slaves than Africans.

Slaves or Indentured Servants

There has been a lot of whitewashing of the Irish slave trade,

partly by not mentioning it, and partly by labeling slaves as indentured

servants. There were indeed indentureds, including English, French,

Spanish and even a few Irish. But there is a great difference between

the two. Indentures bind two or more parties in mutual obligations.

Servant indentures were agreements between an individual and a shipper

in which the individual agreed to sell his services for a period of time

in exchange for passage, and during his service, he would receive

proper housing, food, clothing, and usually a piece of land at the end

of the term of service. It is believed that some of the Irish that went

to the Amazon settlement after the Battle of Kinsale and up to 1612 were

exiled military who went voluntarily, probably as indentureds to

Spanish or Portuguese shippers.

However, from 1625 onward the Irish were sold, pure and simple as

slaves. There were no indenture agreements, no protection, no choice.

They were captured and originally turned over to shippers to be sold for

their profit. Because the profits were so great, generally 900 pounds

of cotton for a slave, the Irish slave trade became an industry in which

everyone involved (except the Irish) had a share of the profits.

Treatment

Although the Africans and Irish were housed together and were the

property of the planter owners, the Africans received much better

treatment, food and housing. In the British West Indies the planters

routinely tortured white slaves for any infraction. Owners would hang

Irish slaves by their hands and set their hands or feet afire as a means

of punishment. To end this barbarity, Colonel William Brayne wrote to

English authorities in 1656 urging the importation of Negro slaves on

the grounds that, "as the planters would have to pay much more for them,

they would have an interest in preserving their lives, which was

wanting in the case of (Irish)...." many of whom, he charged, were

killed by overwork and cruel treatment. African Negroes cost generally

about 20 to 50 pounds Sterling, compared to 900 pounds of cotton (about 5

pounds Sterling) for an Irish. They were also more durable in the hot

climate, and caused fewer problems. The biggest bonus with the Africans

though, was they were NOT Catholic, and any heathen pagan was better

than an Irish Papist. Irish prisoners were commonly sentenced to a term

of service, so theoretically they would eventually be free. In practice,

many of the slavers sold the Irish on the same terms as prisoners for

servitude of 7 to 10 years.

There was no racial consideration or discrimination, you were

either a freeman or a slave, but there was aggressive religious

discrimination, with the Pope considered by all English Protestants to

be the enemy of God and civilization, and all Catholics heathens and

hated. Irish Catholics were not considered to be Christians. On the

other hand, the Irish were literate, usually more so than the plantation

owners, and thus were used as house servants, account keepers, scribes

and teachers. But any infraction was dealt with the same severity,

whether African or Irish, field worker or domestic servant.

Floggings

were common, and if a planter beat an Irish slave to death, it was not a

crime, only a financial loss, and a lesser loss than killing a more

expensive African. Parliament passed the Act to Regulate Slaves on

British Plantations in 1667, designating authorized punishments to

include whippings and brandings for slave offenses against a Christian.

Irish Catholics were not considered Christians, even if they were

freemen.

The planters quickly began breeding the comely Irish women, not

just because they were attractive, but because it was profitable,,, as

well as pleasurable. Children of slaves were themselves slaves, and

although an Irish woman may become free, her children were not.

Naturally, most Irish mothers remained with their children after earning

their freedom. Planters then began to breed Irish women with African

men to produce more slaves who had lighter skin and brought a higher

price. The practice became so widespread that in 1681, legislation was

passed �forbidding the practice of mating Irish slave women to African

slave men for the purpose of producing slaves for sale.� This

legislation was not the result of any moral or racial consideration, but

rather because the practice was interfering with the profits of the

Royal African Company! It is interesting to note that from 1680 to 1688,

the Royal African Company sent 249 shiploads of slaves to the Indies

and American Colonies, with a cargo of 60,000 Irish and Africans. More

than 14,000 died during passage.

Following the Battle of the Boyne and the defeat of King James in

1691, the Irish slave trade had an overloaded inventory, and the

slavers were making great profits. The Spanish slavers were a

competition nuisance, so in 1713, the Treaty of Assiento was signed in

which Spain granted England exclusive rights to the slave trade, and

England agreed to supply Spanish colonies 4800 slaves a year for 30

years. England shipped tens of thousands of Irish prisoners after the

1798 Irish Rebellion to be sold as slaves in the Colonies and Australia.

Curiously, of all the Irish shipped out as slaves, not one is

known to have returned to Ireland to tell their tales.

+++++

There were horrendous abuses by the slavers, both to Africans and

Irish. The records show that the British ship Zong was delayed by

storms, and as their food was running low, they decided to dump 132

slaves overboard to drownso the crew would have plenty to eat. If the

slaves died due to �accident�, the loss was covered by insurance, but

not if they starved to death. Another British ship, the Hercules

averaged a 37% death rate on passages. The Atlas II landed with 65 of

the 181 slaves found dead in their chains. But that is another story.

|

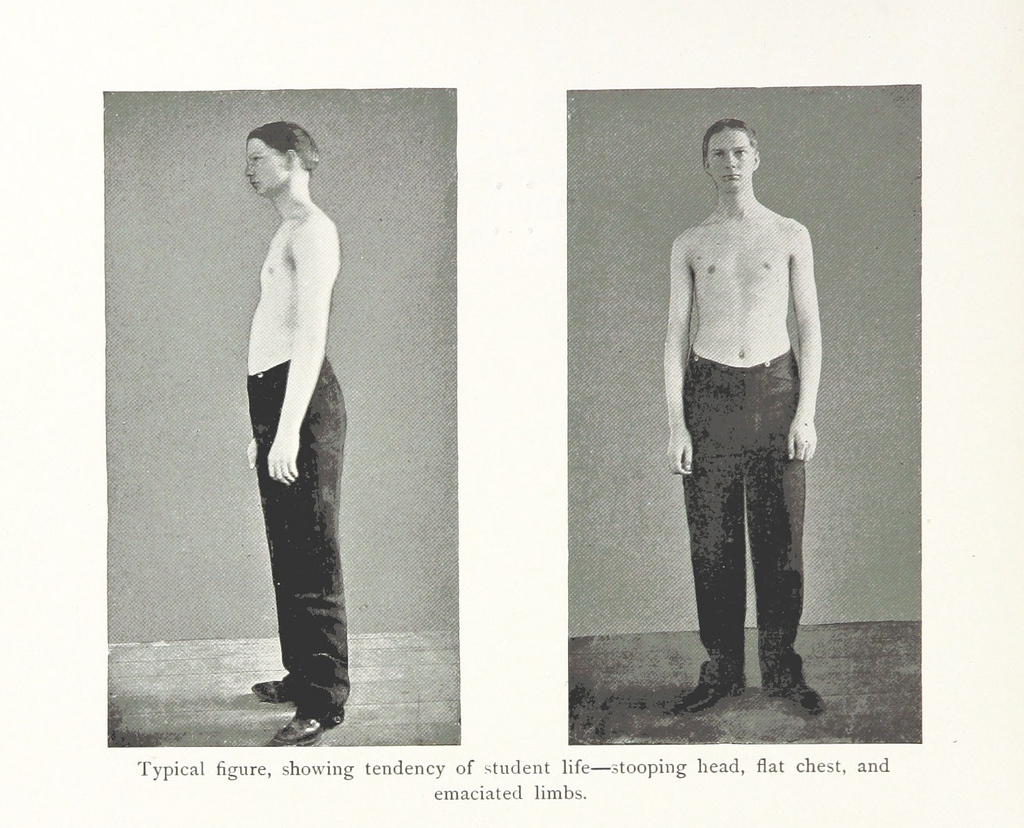

| White slaves |

Many, if not

most, died on the ships transporting them or from overwork and abusive

treatment on the plantations. The Irish that did obtain their freedom,

frequently emigrated on to the American mainland, while others moved to

adjoining islands. On Montserrat, seven of every 10 whites were Irish.

Comparable 1678 census figures for the other Leeward Islands were: 26

per cent Irish on Antigua; 22 per cent on Nevis; and 10 per cent on St

Christopher. Although 21,700 Irish slaves were purchased by Barbados

planters from 1641 to 1649, there never seemed to have been more than

about 8 to 10 thousand surviving at any one time. What happened to them?

Well, the pages of the telephone directories on the West Indies islands

are filled with Irish names, but virtually none of these �black Irish�

know anything about their ancestors or their history. On the other hand,

many West Indies natives spoke Gaelic right up until recent years. They

know they are strong survivors who descended from black white slaves,

but only in the last few years have any of them taken an interest in

their heritage

The economics of slavery permeated all levels of English life.

When the Bishop of Exeter learned that there was a movement afoot to ban

the slave trade, he reluctantly agreed to sell his 655 slaves, provided

he was properly compensated for the loss. Finally, in 1839, a bill was

passed in England forbidding the slave trade, bringing an end to Irish

misery.

British commerce shifted to opium in China.

An end to Irish misery? Well, perhaps just a pause. During the

following decade thousands of tons of butter, grain and beef were

shipped from Ireland as over 2 million Irish starved to death in the

great famine, and a great many others went to America and Australia. The

population of Ireland fell from over 9 million to bottom out at less

than 3 million. Another chapter, another time, another method�. same

people, same results.

Cavanaghs in Barbados

Did the Cavanaghs in Barbados arrive there as slaves? Yes,

definitely. Which Cavanaghs is hard to pinpoint. The registry at St.

Michaels Parish contains the birth and death of a Charles Cavanagh, son

of Charles, which suggests that they were freemen, as records were not

kept for slaves. There is a record of another Cavanagh living on a small

allotment acreage in Barbados, ironically with a given name of Oliver.

(Someone had a sadistic sense of humor.)

|

| White sugar slaves |

Oliver Cavanagh had to be a

freed slave or descended from one, and because his parents are not

noted, they had to be slaves. There are records in Ireland of a number

of petitions filed over a number of years after Cromwell by Mary

Cavanagh, wife of Col. Charles, seeking his pardon and return of lands,

indicating Charles was transported. Recently, Jimmy Kavanagh of Dublin

has found a registry containing over a dozen Kavanaghs in Haiti. Perhaps

someday, we will be able to sort this out, but it is doubtful.

We will explore Charles and Philemon of Virginia in more detail in another article.

We

wanted to know what he had hidden in his drawers. Not his knickers,

which have captivated America's peep-show media, but Massa's file

drawers where he keeps his dirtier secrets.

We

wanted to know what he had hidden in his drawers. Not his knickers,

which have captivated America's peep-show media, but Massa's file

drawers where he keeps his dirtier secrets.