Gillian Tett’s Astonishing Defense of Bank Misconduct

Posted on August 29, 2014 by

I don’t know what became of the Gillian Tett who provided prescient

coverage of the financial markets, and in particular the importance and

danger of CDOs, from 2005 through 2008. But since she was promoted to

assistant editor, the present incarnation of Gillian Tett bears perilous

little resemblance to her pre-crisis version. Tett has increasingly

used her hard-won brand equity to defend noxious causes, like austerity

and special pleadings of the banking elite.

Today’s column, “Regulatory revenge risks scaring investors away,” is a vivid example of Tett’s professional devolution.

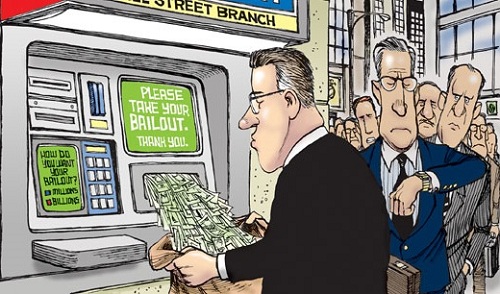

The twofer in the headline represents the article fairly well. First, it take the position that chronically captured bank regulators, when they show an uncharacteristic bit of spine, are motivated by emotion, namely spite, and thus are being unduly punitive. Second, those meanie regulators are scaring off investors. It goes without saying that that is a bad outcome, since we need to keep our bloated, predatory banking system just the way it is. More costly capital would interfere with its institutionalized looting.

In other words, the construction of the article is to depict banks as victims and the punishments as excessive. Huh? The banks engaged in repeated, institutionalized, large scale frauds. If they had complied with regulations and their own contracts, they would not be in trouble. But Tett would have us believe the regulators are behaving vindictively. In fact, the banks engaged in bad conduct. To the extent that the regulators are at fault, it is for imposing way too little in the way of punishment, way too late.

As anyone who has been following this beat, including Tett, surely knows is that adequate penalties for large bank misdeeds would wipe them out. For instance, as many, including your humble blogger, pointed out in 2010 and 2011 that bank liability for the failure to transfer mortgages in the contractually-stipulated manner to securitazation trusts alone was a huge multiple of bank equity. So not surprisingly, as it became clear that mortgage securitization agreements were rigid (meaning the usual legal remedy of writing waivers wouldn’t fix these problems) and more and more cases were grinding their way through court, the Administration woke up and pushed through the second bank bailout otherwise known as the National Mortgage Settlement (which included 49 state attorney general settlements) of 2012.

Similarly, Andrew Haldane, then the executive director of financial stability for the Bank of England, pointed out that banks couldn’t begin to pay for the damage they did. In a widely-cited 2010 paper, Haldane compared the banking industry to the auto industry, in that they both produced pollutants: for cars, exhaust fumes; for bank, systemic risk. Remember that economic theory treats cost like pollution that are imposed on innocent bystanders to commercial activity as an “externality”. The remedy is to find a way to make the polluter and his customer bear the true costs of their transactions. From Haldane’s quick and dirty calculation of the real cost of the crisis (emphasis ours):

In an amusing bit of synchronicity, earlier this week Georgetown Law professor Adam Levitin also looked at mortgage settlements alone and came up with figures similar to the ones that have McCormick running to the banks’ defense. But Levitin deems the totals to be paltry:

In fact, despite McCormick’s and the banks’ cavilling, investors understand fully that these supposedly tough settlements continue to be screaming bargains. When virtually every recent settlement has been announced, the bank in question’s stock price has risen, including the supposedly big and nasty $16.6 billion latest Bank of America settlement (which par for the course was only $9 billion in real money). The Charlotte bank’s stock traded up 4% after that deal was made public. So if investors are pleased with these pacts, what’s the beef?

The complaint, in so many words, is that these sanctions are capricious. Tett again:

So the banks’ unhappiness seems to result from the fact that having been bailed twice by the authorities (once in the crisis proper, a second time via the “get of out jail almost free” of the Federal/state mortgage settlements of 2012), the financiers thought they were home free. They are now offended that they are being made to ante up for some crisis misconduct as well as additional misdeeds. Yet Tett tries to depict the regulators as still dealing with rabbit of 2008 bad deeds that are still moving through the banking anaconda, when a look at JP Morgan’s rap sheet shows a panoply of violations, only some of which relate to the crisis (as in resulting from pre-crisis mortgage lending or related mortgage backed securities and CDOs):

However, the Fed and FDIC earlier this month, in an embarrassing about face, admitted that the “living wills” that banks submitted were a joke, meaning that the major banks can’t be resolved if they start to founder. We’ve said for years that the orderly liquidation authority envisioned by Dodd Frank is unworkable. And we weren’t alone in saying that; the Bank of International Settlements and the Institute for International Finance agreed.

The implication, which investors understand full well, is that “too big to fail” is far from solved, and taxpayers are still on the hook for any megabank blowups. As Boston College professor Ed Kane pointed out in Congressional testimony last month, and Simon Johnson wrote in Project Syndicate earlier this week, that means that systemically important banks continue to receive substantial subsidies.

Yet Tett would have you believe that banks are suffering because investors see them as bearing too much litigation/regulatory risk. If that were true, Bank of America, the most exposed bank, would have cleaned up its servicing years ago.

It’s clear that banks and investors regard the risk of getting caught as not that great, and correctly recognize the damage even when they are fined as a mere cost of doing business. It is a no brainer that their TBTF status assures that no punishment will ever be allowed to rise to the level that would seriously threaten theses institutions. Everyone, including Tett, understands that this is all kabuki, even if the process is a bit untidy. So all of this investor complaining is merely an effort to get regulators to fatten their returns a bit.

Bank defenders like Tett would have you believe that the regulators have been inconsistent and unfair. In fact, if they have been unfair to anyone, it is to the silent equity partners of banks, meaning taxpayers. Banks are so heavily subsidized that they cannot properly be regarded as private firms and should be regulated as utilities. Fines for serious abuses that leave banks able to continue operating in their current form are simply another gesture to appease the public. Yet Tett would have you believe that a manageable problem for banks is a bigger cause for concern than the festering problem of too big to fail banks and only intermittently serious regulators.

Today’s column, “Regulatory revenge risks scaring investors away,” is a vivid example of Tett’s professional devolution.

The twofer in the headline represents the article fairly well. First, it take the position that chronically captured bank regulators, when they show an uncharacteristic bit of spine, are motivated by emotion, namely spite, and thus are being unduly punitive. Second, those meanie regulators are scaring off investors. It goes without saying that that is a bad outcome, since we need to keep our bloated, predatory banking system just the way it is. More costly capital would interfere with its institutionalized looting.

In other words, the construction of the article is to depict banks as victims and the punishments as excessive. Huh? The banks engaged in repeated, institutionalized, large scale frauds. If they had complied with regulations and their own contracts, they would not be in trouble. But Tett would have us believe the regulators are behaving vindictively. In fact, the banks engaged in bad conduct. To the extent that the regulators are at fault, it is for imposing way too little in the way of punishment, way too late.

As anyone who has been following this beat, including Tett, surely knows is that adequate penalties for large bank misdeeds would wipe them out. For instance, as many, including your humble blogger, pointed out in 2010 and 2011 that bank liability for the failure to transfer mortgages in the contractually-stipulated manner to securitazation trusts alone was a huge multiple of bank equity. So not surprisingly, as it became clear that mortgage securitization agreements were rigid (meaning the usual legal remedy of writing waivers wouldn’t fix these problems) and more and more cases were grinding their way through court, the Administration woke up and pushed through the second bank bailout otherwise known as the National Mortgage Settlement (which included 49 state attorney general settlements) of 2012.

Similarly, Andrew Haldane, then the executive director of financial stability for the Bank of England, pointed out that banks couldn’t begin to pay for the damage they did. In a widely-cited 2010 paper, Haldane compared the banking industry to the auto industry, in that they both produced pollutants: for cars, exhaust fumes; for bank, systemic risk. Remember that economic theory treats cost like pollution that are imposed on innocent bystanders to commercial activity as an “externality”. The remedy is to find a way to make the polluter and his customer bear the true costs of their transactions. From Haldane’s quick and dirty calculation of the real cost of the crisis (emphasis ours):

….these losses are multiples of the static costs, lying anywhere between one and five times annual GDP. Put in money terms, that is an output loss equivalent to between $60 trillion and $200 trillion for the world economy and between £1.8 trillion and £7.4 trillion for the UK. As Nobel-prize winning physicist Richard Feynman observed, to call these numbers “astronomical” would be to do astronomy a disservice: there are only hundreds of billions of stars in the galaxy. “Economical” might be a better description.Contrast Haldane’s estimate of what an adequate levy would amount to with how Tett’s article depicts vastly smaller amounts as an outrage:

It is clear that banks would not have deep enough pockets to foot this bill. Assuming that a crisis occurs every 20 years, the systemic levy needed to recoup these crisis costs would be in excess of $1.5 trillion per year. The total market capitalisation of the largest global banks is currently only around $1.2 trillion. Fully internalising the output costs of financial crises would risk putting banks on the same trajectory as the dinosaurs, with the levy playing the role of the meteorite.

A couple of years ago Roger McCormick, a law professor at London School of Economics and Political Science, assembled a team of researchers to track the penalties being imposed on the 10 largest western banks, to see how finance was evolving after the 2008 crisis.Yves here. Keep in mind that these settlement figures are inflated, since they use the headline value, and fail to back out the non-cash portions (which are generally worth little, or in some cases are rewarding banks for costs imposed on third parties) as well as tax breaks.

He initially thought this might be a minor, one-off project. He was wrong. Last month his project team published its second report on post-crisis penalties, which showed that by late 2013 the top 10 banks had paid an astonishing £100bn in fines since 2008, for misbehaviour such as money laundering, rate-rigging, sanctions-busting and mis-selling subprime mortgages and bonds during the credit bubble. Bank of America headed this league of shame: it had paid £39bn by the end of 2013 for its transgressions.

When the 2014 data are compiled, the total penalties will probably have risen towards £200bn. Just last week Bank of America announced yet another settlement with regulators over the subprime scandals, worth $16.9bn. JPMorgan and Citi respectively have recently settled with different US government bodies for mortgage transgressions to the tune of $13bn and $7bn.

In an amusing bit of synchronicity, earlier this week Georgetown Law professor Adam Levitin also looked at mortgage settlements alone and came up with figures similar to the ones that have McCormick running to the banks’ defense. But Levitin deems the totals to be paltry:

There’s actually been quite a lot of settlements covering a fair amount of money. (Not all of it is real money, of course, but the notionals add up).And that is the issue that Tett tries to finesse. The comparison that she and McCormick make on behalf of the banks is presumably relative to their ability to pay, when the proper benchmark is whether the punishment is adequate given the harm done.

By my counting, there have been some $94.6 billion in settlements announced or proposed to date dealing with mortgages and MBS….In other words, what I’m trying to cover are settlements for fraud and breach of contract against investors/insurers of MBS and buyers of mortgages.

Settlements aren’t the same as litigation wins, and I don’t know the strength of the parties’ positions in detail in many of these cases, but $94.6 billion strikes me as rather low for a total settlement figure.

In fact, despite McCormick’s and the banks’ cavilling, investors understand fully that these supposedly tough settlements continue to be screaming bargains. When virtually every recent settlement has been announced, the bank in question’s stock price has risen, including the supposedly big and nasty $16.6 billion latest Bank of America settlement (which par for the course was only $9 billion in real money). The Charlotte bank’s stock traded up 4% after that deal was made public. So if investors are pleased with these pacts, what’s the beef?

The complaint, in so many words, is that these sanctions are capricious. Tett again:

“Now the article does list some abuses, such as the Libor scandal, that were exposed after the crisis. That goes double for chain of title abuses, which suddenly exploded into media and therefore regulators’ attention in the fall of 2010. That means the reason that the penalties have kept clocking up is that, in the absence of having performed large scale systematic investigations in the wake of the crisis, regulators are dealing with abuses that came to their attention after the “rescue the banks at all costs” phase. Those violations are just too visible for the officialdom to give the banks a free pass, particularly since the public is correctly resentful that no one suffered much if at all for crisis-related abuses.

The numbers are getting bigger and bigger,” observes Prof McCormick, who has been so startled by this trend that last month he decided to turn his penalty-tracking pilot project into a full-blown, independent centre. A former leading European regulator says: “What is happening now is astonishing. If you had asked regulators a few years ago to predict how big the post-crisis penalties might be, our predictions would have been wrong – by digits.”

So the banks’ unhappiness seems to result from the fact that having been bailed twice by the authorities (once in the crisis proper, a second time via the “get of out jail almost free” of the Federal/state mortgage settlements of 2012), the financiers thought they were home free. They are now offended that they are being made to ante up for some crisis misconduct as well as additional misdeeds. Yet Tett tries to depict the regulators as still dealing with rabbit of 2008 bad deeds that are still moving through the banking anaconda, when a look at JP Morgan’s rap sheet shows a panoply of violations, only some of which relate to the crisis (as in resulting from pre-crisis mortgage lending or related mortgage backed securities and CDOs):

Bank Secrecy Act violations;Finally, let’s dispatch the worry about those poor banks having to pay more to get capital from investors. If this actually happened to be true, it would be an extremely desirable outcome, for it would help shrink an oversize, overpaid sector.

Money laundering for drug cartels;

Violations of sanction orders against Cuba, Iran, Sudan, and former Liberian strongman Charles Taylor;

Violations related to the Vatican Bank scandal (get on this, Pope Francis!);

Violations of the Commodities Exchange Act;

Failure to segregate customer funds (including one CFTC case where the bank failed to segregate $725 million of its own money from a $9.6 billion account) in the US and UK;

Knowingly executing fictitious trades where the customer, with full knowledge of the bank, was on both sides of the deal;

Various SEC enforcement actions for misrepresentations of CDOs and mortgage-backed securities;

The AG settlement on foreclosure fraud;

The OCC settlement on foreclosure fraud;

Violations of the Servicemembers Civil Relief Act;

Illegal flood insurance commissions;

Fraudulent sale of unregistered securities;

Auto-finance ripoffs;

Illegal increases of overdraft penalties;

Violations of federal ERISA laws as well as those of the state of New York;

Municipal bond market manipulations and acts of bid-rigging, including violations of the Sherman Anti-Trust Act;

Filing of unverified affidavits for credit card debt collections (“as a result of internal control failures that sound eerily similar to the industry’s mortgage servicing failures and foreclosure abuses”);

Energy market manipulation that triggered FERC lawsuits;

“Artificial market making” at Japanese affiliates;

Shifting trading losses on a currency trade to a customer account;

Fraudulent sales of derivatives to the city of Milan, Italy;

Obstruction of justice (including refusing the release of documents in the Bernie Madoff case as well as the case of Peregrine Financial).

However, the Fed and FDIC earlier this month, in an embarrassing about face, admitted that the “living wills” that banks submitted were a joke, meaning that the major banks can’t be resolved if they start to founder. We’ve said for years that the orderly liquidation authority envisioned by Dodd Frank is unworkable. And we weren’t alone in saying that; the Bank of International Settlements and the Institute for International Finance agreed.

The implication, which investors understand full well, is that “too big to fail” is far from solved, and taxpayers are still on the hook for any megabank blowups. As Boston College professor Ed Kane pointed out in Congressional testimony last month, and Simon Johnson wrote in Project Syndicate earlier this week, that means that systemically important banks continue to receive substantial subsidies.

Yet Tett would have you believe that banks are suffering because investors see them as bearing too much litigation/regulatory risk. If that were true, Bank of America, the most exposed bank, would have cleaned up its servicing years ago.

It’s clear that banks and investors regard the risk of getting caught as not that great, and correctly recognize the damage even when they are fined as a mere cost of doing business. It is a no brainer that their TBTF status assures that no punishment will ever be allowed to rise to the level that would seriously threaten theses institutions. Everyone, including Tett, understands that this is all kabuki, even if the process is a bit untidy. So all of this investor complaining is merely an effort to get regulators to fatten their returns a bit.

Bank defenders like Tett would have you believe that the regulators have been inconsistent and unfair. In fact, if they have been unfair to anyone, it is to the silent equity partners of banks, meaning taxpayers. Banks are so heavily subsidized that they cannot properly be regarded as private firms and should be regulated as utilities. Fines for serious abuses that leave banks able to continue operating in their current form are simply another gesture to appease the public. Yet Tett would have you believe that a manageable problem for banks is a bigger cause for concern than the festering problem of too big to fail banks and only intermittently serious regulators.

No comments:

Post a Comment